All the architects I know love books and most have an addiction of buying and keeping their books on display. I frequently receive requests from people to share with them the books I am currently reading but since I don’t have time to read any of the books I buy, I’ve asked long-time friend, fellow architect, business partner and bibliophile Michael Malone, AIA to share which books he is currently reading. As an added bonus, he even agreed to write up a book review for us.

Robert Moses and the Modern City: The Transformation of New York

Edited by Hilary Ballon and Kenneth T. Jackson

Published by W. W. Norton & Company, 2007

The gold standard for 20th century biography is Robert Caro’s exhaustive and pain stakingly researched The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for his effort, Caro went on to write an equally detailed biography of President Lyndon Johnson, with four completed volumes thus far and at least one more to come. A stickler for original source research, Caro set a standard with his Moses book that not only shed light on the man, but created a complete picture of those who championed and supported him, challenged him and ultimately removed him from power. Caro created a portrait of a driven, manipulative and vindictive man obsessed with power, his own vision and its execution no matter what the consequences. As ruthlessly as Caro portrayed him, the reader was still left with a sense of awe and wonder at what Moses accomplished and were rewarded with a portrait of mid-century America that few others have been able to capture.

This book, edited by Hillary Ballon and Kenneth T. Jackson, also including collected expert writing from a variety of sources, takes a decidedly revisionist view of Moses, informed by the position New York now enjoys in the world and the way Moses’ many projects and interventions support it. A primary thesis of the book is the understanding that the many projects completed under Moses’s leadership are integral to the way the city functions now, in fact are essential for the modern metropolis. Sections of the book are written by various experts and historians who haves studied and assessed the vast selection of Moses projects and have an understanding of how they function today.

While taking a nuanced view of Moses’s work, it remains honest about his short comings and the less salubrious aspects of his character. His contempt for those who challenged him is fully addressed, but there’s an oddly forgiving analysis of his racist views that blithely affected many people’s lives, framing it as emblematic of the times. Likewise his commitment to transportation solutions that focused on the automobile at the expense of mass transportation is dismissed as reflecting federal funding priorities of the times.

For those interested in Moses and his career one wonderful aspect of the book is the catalogue of projects by types: parks, parkways, bridges, pools, Title 1 housing and other projects, among them the UN headquarters and Lincoln Center, both in Manhattan being two of the most exemplary. Detailed descriptions and outlines of the circumstances of each project are provided, as well as key project team members and consultants. Reading this portion of the book gives more cause for admiration than disdain and certainly supports the idea that New York needed someone like Moses to provide the framework for the city to function in the modern world.

Finally the book addresses the projects that contributed to the New York City the world knows and understands, many of its attributes made possible by Moses’s singular ability to focus and find a path where others saw only obstacles. It may be a dubious assertion, but with his myriad responsibilities and the resources at his disposal it’s hard to imagine anyone else having the authority, let alone the imagination. It also supports the idea that it takes real genius to push through major construction initiatives in a functioning democracy.

Moses remains a controversial figure, but between this book and Caro’s a more complete understanding of a man and his times can be formed and understood. This may not be the final such effort but it’s a valuable way to review and understand an amazing and in many ways admirable (if tarnished) public career.

The Architecture of Harry Weese

Robert Bruegman with Building Entries by Kathleen Murphy Skolnik

Published by W. W. Norton & Company

To college students of the late 1970s and early 1980s the second wave of post war modern architects like Harry Weese were largely ignored, or worse for all intents nonexistent. This group of distinguished practitioners which included Paul Rudolph and Edward Larrabee Barnes, that didn’t easily adopt or move to the tenants of then prevailing post modernism was for a short time lost, their thoughtful and interpretive modernism considered irrelevant. In the reconsideration of architecture in regards to context, historic meaning, and buildings conveying language, old line formal modernism offering a revolutionary way of life was for a short time lost. Fortunately times have again changed and these architects and their work are being rediscovered. Time for thoughtful assessment is well overdue and fortunately the body of scholarship is growing, sadly at a time when many of these projects are being lost.

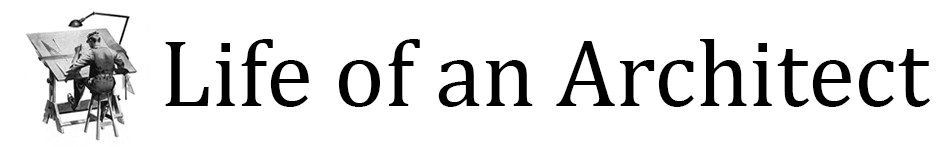

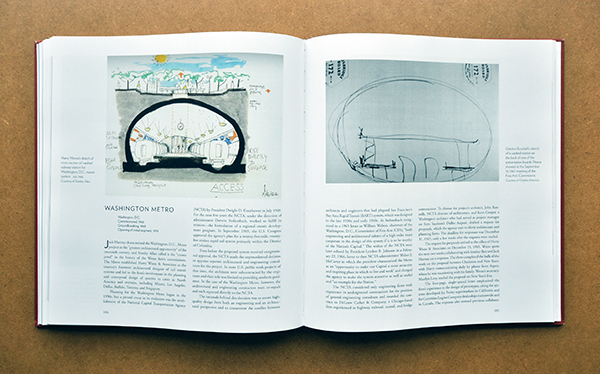

Chicago architect Harry Weese may be best known for his masterpiece the Washington DC Metro system stations, whose beautiful barrel vaults form some of the grandest civic spaces of the 20th century. If this were Weese’s only achievement he’d be assured a lasting and deserving legacy, but as this wonderful book by Robert Bruegman illustrates he was an inventive and thoughtful humanist, concerned as much with how people used and perceived his spaces as their aesthetic implications for other architects. Practicing in a Chicago heavily influenced by Mies and to a lesser extent his progeny, CF Murphy among them, Weese applied modern design precepts to older, more accessible materials resulting in an architecture that was warm and engaging, rarely polemic. Even when making modernist buildings Weese revaluated and explored the prototypes to come up with something inventive such as his office buildings for IBM and Time Life. A pioneer of adaptive reuse, Weese found beauty in old loft buildings and established prototypes for their conversations to homes and workplaces. Among his many achievements was a sensitive restoration of Louis Sullivan’s Auditorium Theater, saving it from possible demolition.

Bruegman also sheds light on Weese’s entrepreneurial ventures, first in setting up a successful modern design store with his wife Kitty and later acting as a developer, often for projects that required vision the market wasn’t ready to recognize. Weese further dedicated a life to working on ways to enhance and enliven life in his beloved Chicago, even acting a developer to encourage the building of middle class houses in the core of the city itself.

The partial catalogue of the Weese firm’s work included in the book with project descriptions by Kathleen Murphy Slolnik provides photos and insight into several significant projects. One wishes it were more extensive and detailed and suggests a more comprehensive monograph on Weese is still needed. Weese was genuinely inventive in his building’s planning and cross sectional development and this deserves additional study and documentation.

At the end of his life Weese faced personal and health problems that left him unable to work productively in his firm. The book is candid in its discussion of this tremendously talented man and both his successes and shortcomings. Perhaps his real legacy is yet to be understood but in part it is represented by the many excellent firms planted by his former staff and in many cases nurtured by Weese himself. One is left with the impression of a warm and engaging man who enjoyed life enormously and perhaps impacted the people around him and his clients more than his buildings did.

.

.

Disclosure of Material Connection: I received the books reviewed above for free – Michael actually hand selected them himself from a massive list of books – with consideration that they might be shared with the people who read my site. I have also included affiliate links to these books, which means if you click on the link and end up buying the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. I am disclosing this because I am an honest guy, but also because it is in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.”