There is a secret that all attentive architects know: Don’t give your client what they ask for, give them what they need. Better yet, have them be a part of the design process.

In order to create personal and successful designs, you need to develop a relationship with your client that goes beyond providing functionality solely based on their requests. Unless you are designing for troglodytes, there will probably be bedrooms, bathrooms, a kitchen, some living areas, and sometimes the odd side room etc – but it’s important to understand how each client will want to use these spaces in order to give them what they want. The aim is to create a home that is uniquely theirs, reflects their personality, and has been designed according to how they will live and occupy each space. Unfortunately, what a client needs is not necessarily what they ask for … and it’s up to me to know the difference.

Part of my role as architect is to be an interpreter and translator – to listen to what the client is saying and then to digest, interpret, prioritize and re-issue that information back to them. The goal is to ultimately protect the client from themselves, scrape away all the nasty bits of conflicting thoughts and imagery they have been assembling, and present back to them a clearer and more representative picture of what they are after. I truly believe that design professionals are better at the job when they are able to develop a personal relationship with the client along the way; It makes it easier to help them create a house that suits the way they really live, instead of how they think or hope to live.

This isn’t anything that I haven’t said in one form or another several times on this site … but I was struck by something the other day that made me pause and think about it and it’s relevance to how I practice architecture – or at least how I want to practice architecture. We don’t design buildings for ourselves, we have clients. Frequently those clients have come to us because they’ve seen what we can do and they’ve decided that they think we are a good fit for them and their project. Sometimes that means you get hired to do the same sorts of projects as you’ve already done. It’s not all that uncommon that a new client will point to one of our projects and say “I want this” … but not always.

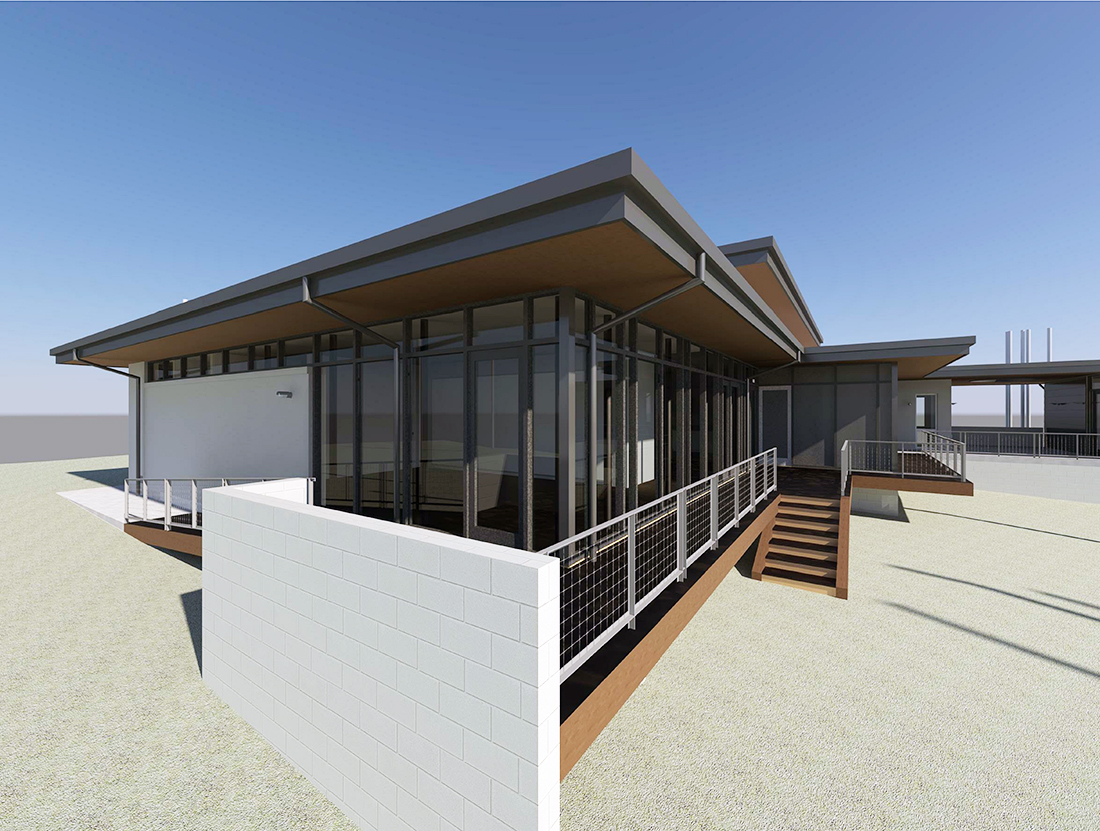

Sometimes these new clients come to us based on the experience of a previous client – and since a vast majority of our work is based on personal relationships and word of mouth – this new client isn’t as familiar with our work or with the full range of our abilities. We currently have a project in the office that is in the design development phase, that is an interesting mix of traditional and modern, and that is fairly different than the other work you might find if you searched through our website. In the case of this project, there isn’t another project that this particular client pointed at and said: “I want this.”

So how do these projects come to be? How and why do these folks come knocking on our door? I can only assume that we haven’t been identified with a particular style and as a result, only get asked to do that sort of project. (That and the fact that most people seem to like working with us.)

The project I’ve shown up to this point is just being developed but it isn’t very hard to see that it doesn’t look a thing like the KHouse Modern project I’ve been covering on the site here for a while. But they shouldn’t look like one another, right? These projects were done for different clients, in different parts of the country, and with different aesthetic goals. In fact, I think the only commonality between the two is us … the architects.

I know that there are architects out there whose practice exists to create a certain identifiable product. Most architecturally trained people could tell if they were looking at a Frank Gehry or Zaha Hadid project … but I am not Frank Gehry or Zaha Hadid. While I might want their bank accounts, I struggle with their projects on many levels, one of which is that the work is so identifiable with the architect, and not the person or place with whom they are serving.

Believe me, I am not passing judgment on those architects … they are creating more than just architecture. Meanwhile, I am still enamored with the idea that the client is still in there somewhere – that they are getting what they want while still getting a little bit of me in their project (that sounds different from how I imagined it in my head).

I’ll also confess that part of the reason I have been thinking about this is due in no small part to the last post I wrote – Schematic Design isn’t “Architecture”. I shared this post on a LinkedIn forum and I was summarily told I was wrong … that Schematic Design is indeed “Architecture”.

To summarize that post in a few words, I was at a meeting with some new clients and we were developing the programming (what rooms, spaces, and functions would be needed) and going through the beginning stages of schematic design (adjacencies of the programming and initial aesthetic conversations). As I was sitting there with the clients going through the process, I mentioned that we were “diagramming” the house and that it was great that the clients felt comfortable enough to take the pen and sketch out their own ideas as we were talking through the creative process. During this time of creative collaboration, we would be sketching diagrams to clarify our talking points and I would say “This is a diagram, this isn’t architecture. Your house will not look like this.” I don’t know about you, but I thought that the experience was pretty cool. Right?

Well, not according to a lot of the people in this particular LinkedIn forum. I was told:

- “The problem with sketching in front of the client is that they can get attached to something I will want to revise later.”

- “The question is when to get compensation and for what ‘Architectural’ work. The problem here is not Schematics but Semantics. Be clear boys and girls, be very clear and don’t give away the farm too soon.”

- “No client has the patience to be part of that process. That’s why you need to keep them focused on the questions you want to focus on.”

- “No wonder architects are undervalued if they don’t consider their own design work architecture.”

- “Schematics is architecture. It is the basis of architecture. It could be submitted as evidence of design intent in a court of law if you drew one schematic but delivered a different more completed design later.”

While none of these comments changed my mind to my assertion that schematic design isn’t an end to a means, but part of the journey. The “Start” of the journey. Maybe using “Quotation Marks” around words is confusing for some people – I don’t know. I’m not entirely sure some of those people actually read the article because their comments seem ludicrous.

I read those comments and I thank my lucky stars that I get to practice the way I do. I haven’t felt the need to put up barriers to protect myself from the client. I still think collaboration is the best way to have a successful project. It is the thing that allows me (and the office where I work) the opportunity to design different sorts of houses for different sorts of people. Maybe trying to like your clients more than your buildings creates the sort of practice where I think it’s cool to sit around a table and pass a pen back and forth with the clients. Besides, if the clients want to do something that I think is a mistake, shouldn’t I be able to explain why they shouldn’t do it? I suppose I am the parent in this relationship and it’s my job to protect the client from themselves – but not by excluding them from the process, but through educating them on the process.

So far, I think I’m doing it the right way.

Cheers,