When you pull up in front of a house, did you know that you can determine if the house is modern even before look up? Just a look at the sidewalk. If the sidewalk is in a continuous pour from the street to the front door, someone didn’t get the Bob Borson memo on modern sidewalks.

Despite the fact that I’ve been designing residential sidewalks for a long time, I’ve don’t think I’ve ever poured an uninterrupted concrete sidewalk that led up to the front door of one of my projects. Instead, I like to pour individual floating pads of concrete to help modify the scale of the approach so that you aren’t walking along a concrete landing strip. So that’s what I thought I would talk about today – how we build concrete sidewalks out of individual pads of concrete.

The image above is a landscape plan for one of the houses we currently have under construction. We worked with a landscape architect on the layout and planting, but the sidewalk layout is something that we put together in our office from the beginning. One thing that I don’t have to consider too often as a design parameter is accessibility and snow. I’ve personally navigated pads like this in a wheelchair so I know it’s possible without much effort, and the amount of snow we get here doesn’t make shoveling snow an issue.

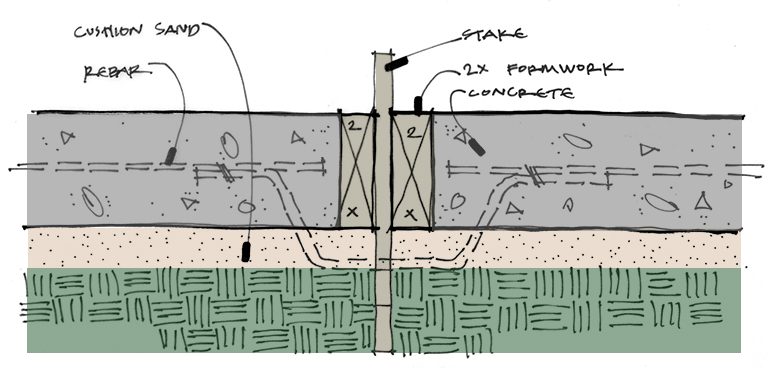

This formwork for this entire sidewalk came together in about 3 hours (I think there 15 people on site and working on this single sidewalk). All of this was framed up using 2×4 and 2×6 lumber, 3/4″ stakes, and #3 rebar. *Did you know* The rule of thumb I use on rebar is to multiply each number by 1/8″ … meaning #3 bar is 3 x 1/8″ or 3/8″ thick.

This is looking down at the formwork that surrounds where two floating pads come together. We generally go for a 4″ max spacing for the gap but more times than not, it is exactly 3 3/4″ wide. This accounts for each 2x framing member with a 3/4″ stake driven in the middle to hold the formwork in place.

One of the things that we do that might be a little bit different, is that we tie all the floating pads together by tying the rebar from each floating together with its neighbor. How do we do that? If you look at the picture above, you can see that a small channel has been dug out underneath the formwork and there is a bent piece of rebar that is fed through that channel.

Here’s a closer look at the steel that has been bent – this is not where it will go, I pulled it out of the channel so I could take this picture.

I sketched up a detail to show you better what I am describing. I didn’t draw this detail up for this particular contractor – he and I have worked together long enough that he knows how to execute this particular detail. You can see the dashed lines up above that represent the rebar (which is just short for “reinforcing bar”). Each floating pad has its own rebar in it – you can see where I’ve sketched in the bent rebar that goes under the formwork but comes up high enough that it will tie off to the steel in each concrete pad. The other added benefit of this particular method is that it helps ensure that the concrete doesn’t get pushed down to the bottom of the sidewalk, rendering it useless.

I will go ahead and state the obvious … the steel rebar that is exposed in the ground will eventually rust and that rust will migrate its way into the concrete. This is not a detail I would use in many parts of the country, and depending upon the environmental elements, the rate at which the rust occurs will vary. As it is, it will take a very long time for this mild steel to rust and become a problem here in Dallas.

Of course, you don’t have to tie the pads together – we just do it so that over the next few years as the construction settles, the concrete pads will move in unison.

We have a few grade changes in our sidewalk and when that occurs, the edge of the concrete thickens to make up the difference in the grade change. The picture above is what the step looks like in the formwork. If you look closely, you can see how the top 2×6 boards are sitting on top of another 2×6 board that is tapered

Here is another view of the formwork used to create the step.

Fast forward a few days and the concrete has been poured, and cured enough that they have removed all the formwork. The other thing that has been done is that all the concrete has been acid-washed. We generally do not want to see broom-finished concrete (a process of creating surface texture on the concrete by literally dragging a broom across the surface while the concrete is still setting). We typically like to see acid-washed concrete because of the consistent clean finish you get as a result. I did not see how this surface was etched but most of the time I see the concrete contractors using muriatic acid mix in a 4 parts water to 1 part muriatic acid.

Here’s a look at the finished concrete pads leading up to the front door.

The site has not even been rough graded yet but eventually the surrounding dirt will be set about 2″ below the top of the concrete

I will admit that I have never drawn this detail in my life, and the first time I ever saw it done this way was probably 10 years ago when I was working on a project with a Dallas Landscape Architect Kelly James – a great guy who passed away in 2006. Over the years I have kept my eyes open for a better way to detail these floating pads and have yet to see one. If you have any tips of tricks, feel free to share them with me.

Cheers,