If you are an architectural student – or a young architecture school graduate – Architectural Portfolios are extremely important. While they are probably not as important as you think, they are far more important that what most people outside the industry realize. This is the tool that will play THE key role in getting a job … the right sort of job. Resumes are important, they can help you get an interview, but few people coming out of architecture school will ever get hired based on their zippy resume.

It all comes down to your portfolio.

The problem is that most people:

a) don’t know how to put a decent portfolio together, and

b) focus on the wrong sort of message in their portfolio.

Since it is that time of year and my inbox is starting to get clogged with portfolios that people email me blindly, I thought I would provide some insight into what people (like me) are really looking at when they see your portfolio. I can almost guarantee you that it isn’t what you think.

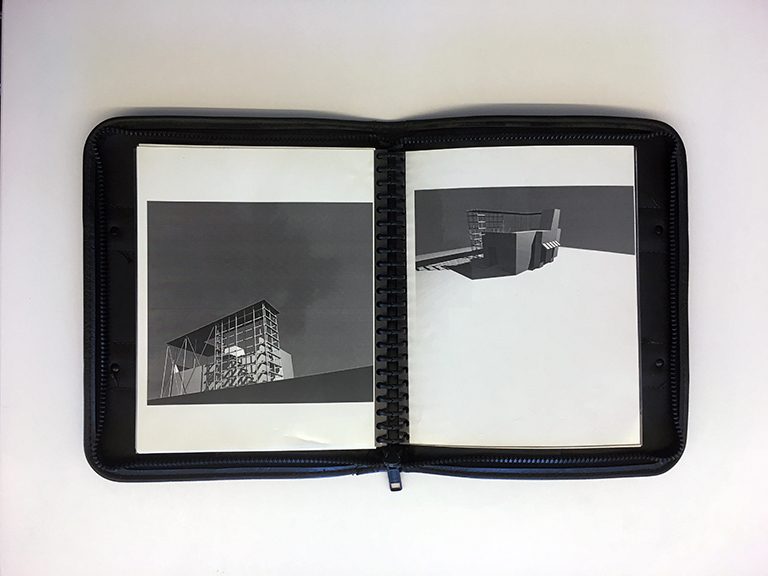

When I graduated from architecture school, 25 years ago, things were a lot different. People didn’t have digital portfolios, and you didn’t have the option of creating a website where people could review your work. Just looking at my portfolio (above) reminds me of just how far things have come. At the time, my portfolio was pretty nice. It’s important to realize that at this time, most portfolios were assembled using copies, physical photographs, and glue to adhere them to the pages. Just remember that the first version of Photoshop 1.0 was shipped in 1990, just two years before I graduated, and the first time I saw it available for use on a PC was in 1995. Manipulating digital images for college students just wasn’t an option. That’s not true anymore and with the number of digital options available to just about everyone, incorporating digital technology into your portfolio should be a given.

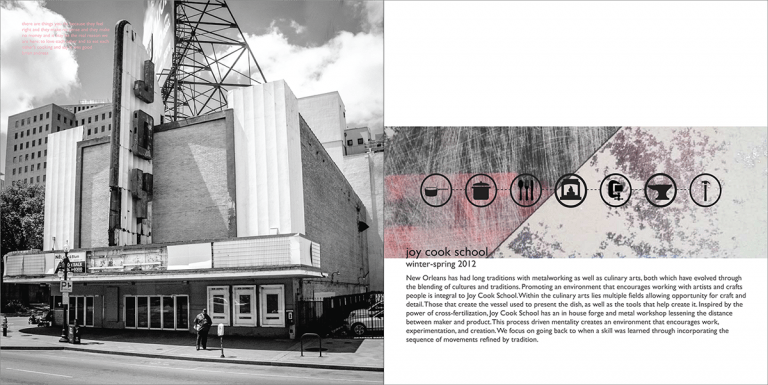

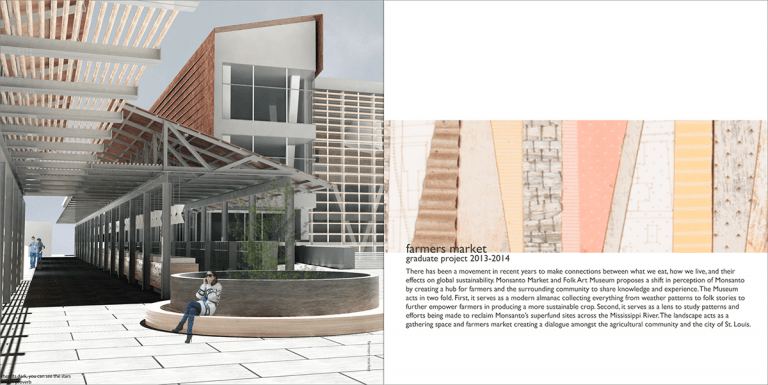

To assist me in my conversation today, I am going to show you an example of one of the best portfolios I have ever reviewed. This is from Danielle Anderson, who is currently working in my office. Hmmmmm, imagine that. One of the best portfolios I’ve ever reviewed was from a person who was ultimately hired to work in our office. In fact, she’s currently sitting about 8 feet away from me as you read this (assuming that you are reading this during regular business hours).

I’m not going to show you every single page from Danielle’s portfolio, but I am going to show you examples from her portfolio that demonstrate what people like me are really looking at when we review portfolios.

Curate the Content

Danielle’s portfolio contains around 54 individual pages but feels much shorter when it is viewed in booklet form – two pages on display at once. She did not include every single project she ever designed from her time in school – which is the first thing you should consider. You need to carefully think about which projects, and how many, you want to include in your portfolio – pick only those that are supported with the visuals that tell the story you want to tell.

For example – I have no idea what’s going on in the images above … but that doesn’t really matter. The first time I look at someone’s portfolio, I might spend a maximum of 5 seconds on any given page. What I do notice from these images, is how they are laid out on the page, the balance of positive and negative space, the balance of white versus image – something that will be readily apparent on many of Danielle’s pages. I see care and attention to craft, and even though I am early on in this portfolio, I can make certain assumptions about her digital skills just by evaluating how she has edited the photos.

Let Your Images Tell the Story

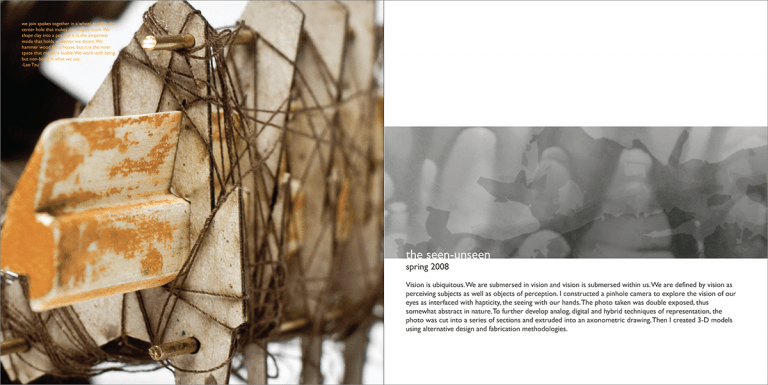

You should consider how much text you decide to include in your portfolio … because I probably won’t read it the first time I flip through your pages. This is something that I think about every time I look at a portfolio … or even write one of my blog posts. Most people like to look at the pictures, and if the images are evocative enough to catch someone’s attention, you might get them to go back and read the small bit of text associated with that image. The takeaway here is that you need to rely on your pictures and graphics to draw in the people who are reviewing your portfolio.

This is an example of curating the imagery being used to maximum effect. There is a lot of white space on these pages, but they don’t feel empty. When you are using graphics to tell the story, make sure that you only include items that are specific to the narrative they were created to tell. If they don’t contribute, eliminate them.

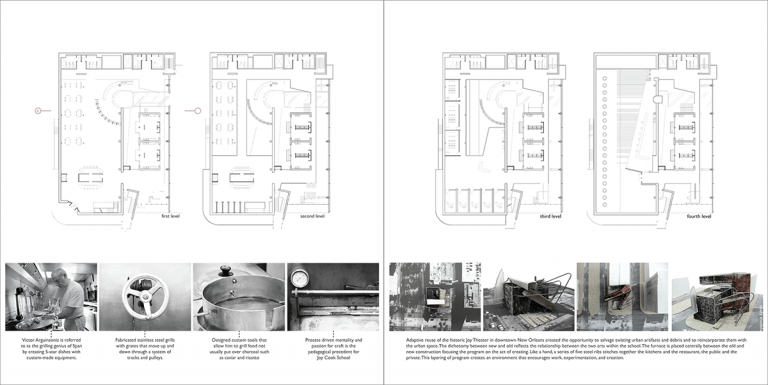

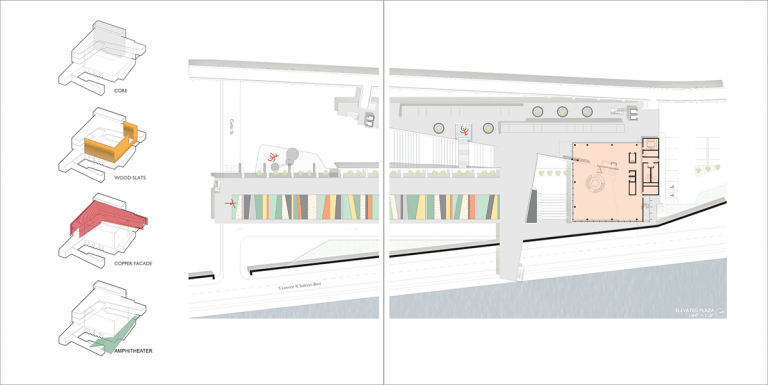

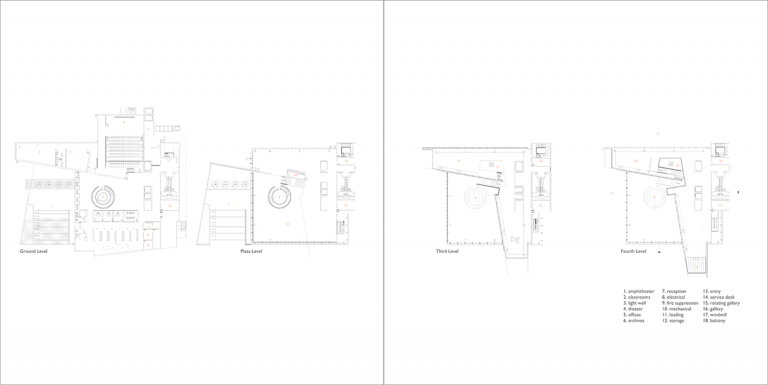

In Danielle’s portfolio, she only included a handful of plans and only two major architectural projects. On these pages, the drawings are clearly the star, and she was smart to remove all the superfluous information from the drawings she included so that they come across as diagrammatic. She wasn’t including these drawings to demonstrate her ability to annotate a plan, so I don’t need to see a bunch of dimension strings.

Here is another example of finding the right balance between positive and negative space on the page. One of the strengths of Danielle’s portfolio was the extremely clean graphics she assembled to tell her story. More times than not, I am not reviewing the actual design, but rather the way she assembled the story and chose to illustrate that story. I can ascertain as much about her design abilities just by evaluating all the things she didn’t show as I can from the things that she did show. This is how you effectively curate the content within your portfolio.

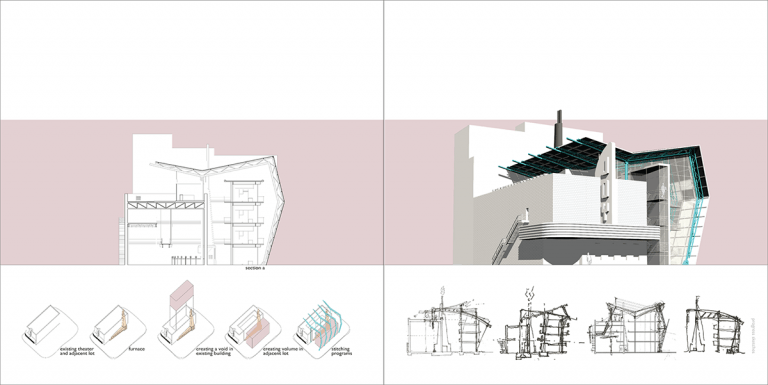

Be Consistent in your Graphics and Layouts

This is the second, and last, major architectural project Danielle included in her portfolio – and I decided to include it only to demonstrate how consistent Danielle was when it came to designing her layouts and then sticking with them through her portfolio.

Demonstrate your Graphic Fluency

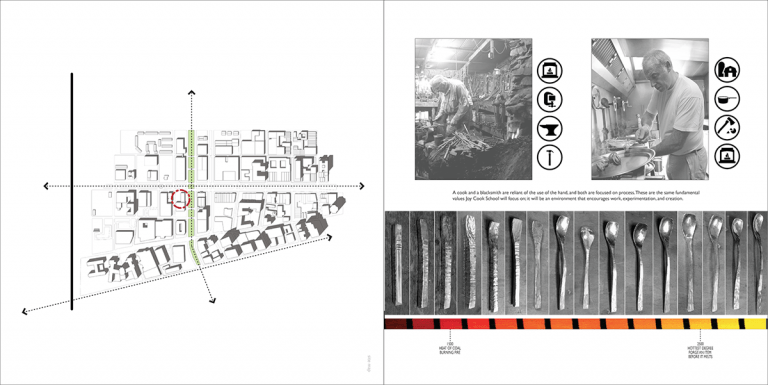

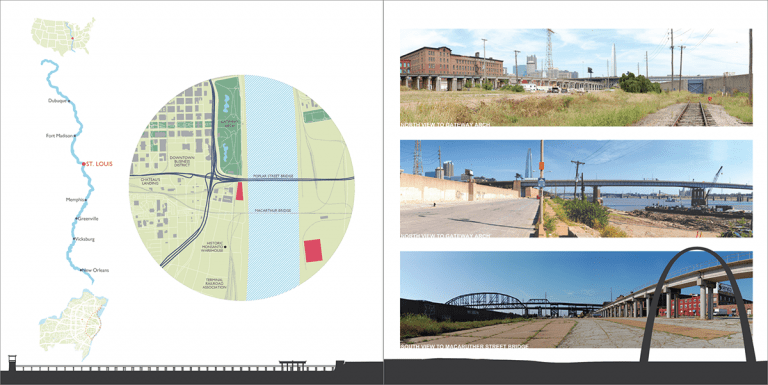

Even though at the time this was the portfolio of an architectural student, it has the visual sensibilities of a graphic designer. There are icons and wayfinding devices scattered throughout. In just a moment, I can look at the drawing above – something as simple as a site plan – and completely understand the geographic location of this project within the context of the country, to its place on the river, its context to a neighborhood, and finally its relationship to a historical marker.

Unless this is the first time you’ve ever read an article on my site, you already now that I am extremely particular in my use of graphics when it comes to drawing. The use of line weight is very important in architectural drawings and I can promise you that if you don’t use it, I’m not going to look at your drawings for very long.

Because this article has a lot of images in it, and I didn’t want it to take a million years to load, I haven’t done Danielle any favors by lowering the graphic quality of her drawings … I can assure you that her drawings included effective use of pen weight. If you look at the plans shown above, it takes a lot of restraint to keep these sheets so minimal – a few plans and a room legend. I can count on one hand the number of portfolios I’ve received where this level of restraint was demonstrated … and it didn’t go unnoticed. These are actually very evocative plans and since they are placed on a page by themselves, there wasn’t any visual competition for my attention.

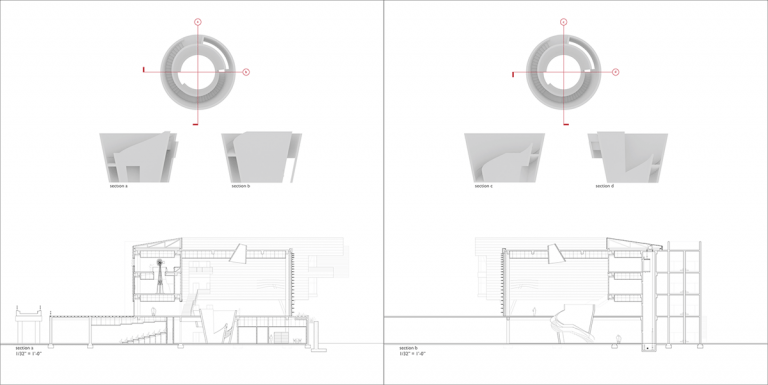

I mentioned previously that you need to curate the content of your portfolio as a way of controlling the story you are trying to convey. It was important to include a few building sections for this project and all you have to do is look at the drawings above to see why. I’m not evaluating whether or not Danielle correctly illustrated her structural systems, but I do like to see that how this building was designed included a consideration for how it would be built.

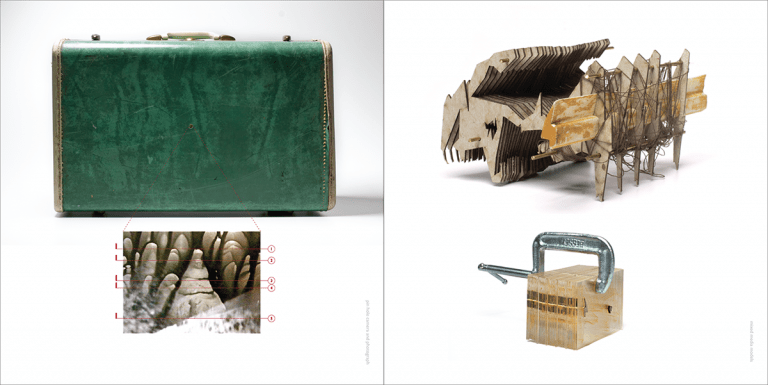

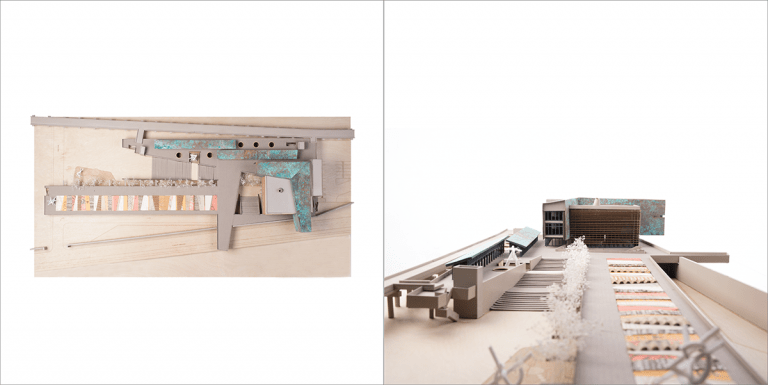

Models … include at least one

While it would seem that fewer and fewer students build models these days, I like to see them in any portfolio I am reviewing. Looking at a model that you made does more than just allow me to reminisce about the good old days … it tells me something about your attention to detail, your ability to focus on a fairly mind-numbing task for an extended period of time, and I can look at how your model was built from a craft standpoint – which tells me something about you as an individual. Do you care enough about your work to make sure that things are glued down properly? That all the teeny-tiny elements are properly aligned to one another? What about your decision-making process on how to articulate the materials within your model?

Physical models are just another way for me to evaluate your design aesthetic. You have to decide how to present it, what sort of base is it sitting upon, what shape is the footprint of the model? I don’t know if you’ve noticed this, but none of the items I’ve been talking about have anything to do with the actual design. I am not judging your architecture, I am examining your thought process about how you communicate an idea and demonstrate pride in your work.

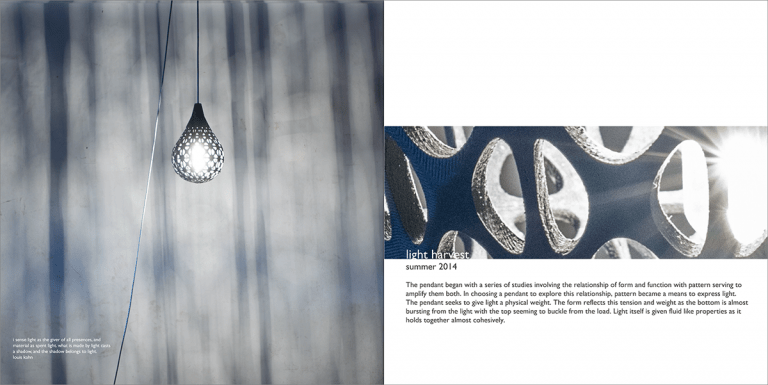

Include Something that isn’t a Building

It is hard for me to truly evaluate a building design project presented in a portfolio. For all I know, your studio professor made all the hard decisions for you … or maybe you were the weakest member of the team jointly working on a project. For these reasons, I like to see something from your time in school that isn’t a building.

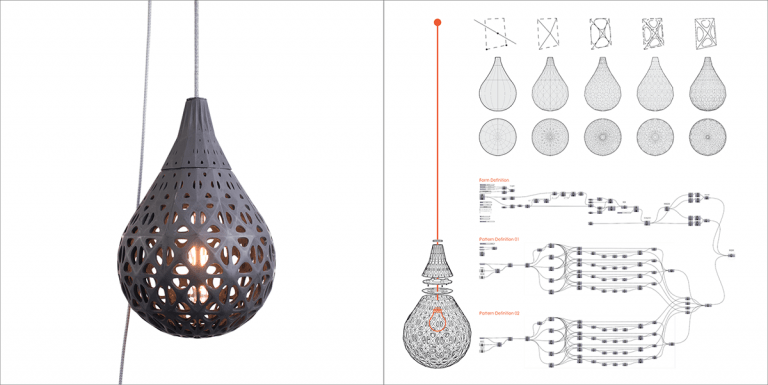

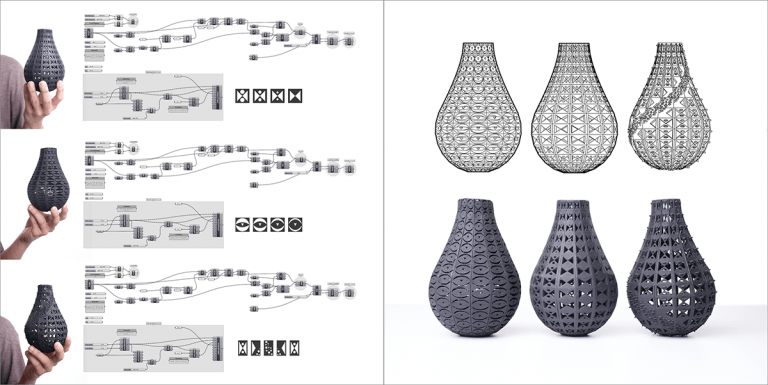

I suppose it is still possible that Danielle’s professor disproportionately helped her with this lamp project, but I can still see examples of a consistent design process at work here. Most obviously, there is the graphic nature of how these pages are laid out and how the information is presented. Even a dinosaur like me knows what parametric modeling looks like, and I can look at an evolution of decisions being made in how this work is presented.

These are very strong pages graphically, with the only apparent item of disconnect being that the bottom right lamp not being rotated to match the graphic directly above it. (and I can promise you that when Danielle reads today’s post, she will admit that she already noticed this)

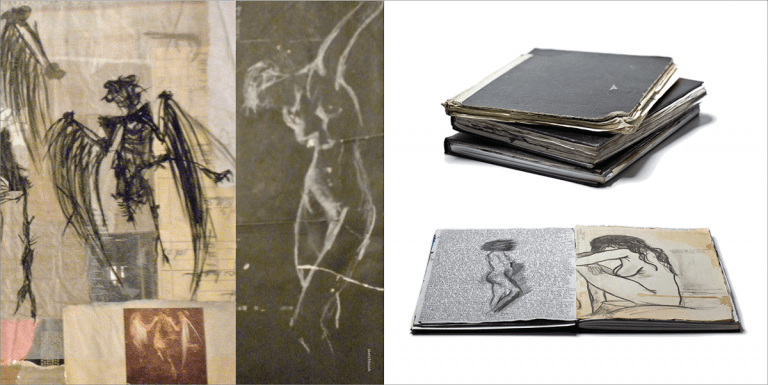

Include Something You Created by Hand

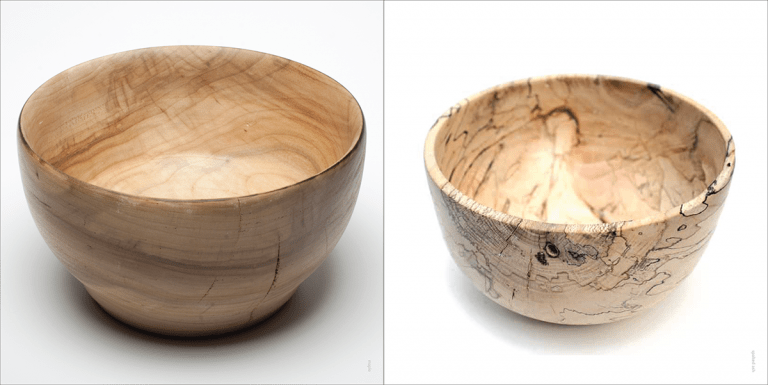

This is definitely old school, but for me, I really want to see something that you did without using a computer. There seems to be a disconnect these days between modern architectural educations and the idea of the Architect as a “Master Craftsman”. One of the most important sections you can include is something that you did or created, that didn’t involve clicking some buttons and moving a mouse around. Show me some sketches, maybe you built a kayak, restored an old car, maybe you take and develop your own pictures (I know, who develops pictures anymore?…) This is the one area of your portfolio that can be used to tell me something about who you are, and the things that interest you, that go beyond the courses you took in college. If someone included a picture of a handmade Stormtrooper costume that they made, it would interest me.

Maybe you took wood shop and learned how to turn wood on a lathe … anything, really. Do not pass up on the opportunity to express yourself.

The last item I would like to go over is my thoughts regarding the format of a portfolio. I don’t think it’s all that complicated so I saved it until the end because it will only take a few sentences to cover. You should have one printed out version of your portfolio that you can bring with you on your job interviews. Once you get your first job, that portfolio will most likely be relegated to a shelf in your apartment for all eternity because nobody cares what you did in college once you are a few years removed from graduating.

You should have your portfolio available for viewing digitally online somewhere. Danielle’s portfolio was 154MB in size and I’d be really irritated if someone tried to email me a portfolio that size. You could make it a shared file on your Google Drive, or you could establish an account at sites like Issuu that can house your online portfolio (they have a free plan that would work for most and a slightly more flexible version that will run you something like $20/month … but you won’t need it once you have that job, right?)

I have strong opinions about how you should reach out to a potential employer, and first contact should not include your portfolio – and therefore, a “mini” version of your portfolio is not needed. Try calling first to a) find out if the firm is hiring in the first place, b) find out the name of the person you should address your resume, c) learn/ask how they might want to see your portfolio. This is problem-solving 101 and whenever I receive an email that starts off with “Dear Sir/Madam” I don’t even bother to read the rest of it.

[DELETE]

Of course, I’ve already written about resumes before. If you haven’t read it, do everyone a favor and go read it – I promise it will help – just click here or on the graphic below.

Now that I’ve shared my thoughts with how portfolios are really reviewed, feel free leave a comment on all the considerations I might have missed – I would truly welcome reading them. The most important message that I wanted to convey with today’s post on architectural portfolios, is that the people who review them are probably not focusing on the architecture – at least, not at first. There are so many things I can tell about someone by looking at all the things “around” the architecture, that I’ll save the architectural crit to the time when you come into the office for an actual interview. Even then, I’ll be focusing on how you answer the questions, how you articulate your ideas, the words that you choose … then, maybe, I’ll take a closer look at the design for your “Dark Side of the Moon Lifestyle Habitat Pod.”

Best of luck,