Architects talk about design a lot – most of us go to school because we believe that we will become architects that design buildings. When it comes to design, most architects design until the drawings leave the office and never look at the clock or associate their fees with how much “design” they will be providing … so why is there so much bad architecture out there? That’s just a part of what we will be discussing today in Episode 77: Design Better.

[Note: If you are reading this via email, click here to access the on-site audio player]

Podcast: Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn

What Does “Better” Even Mean? jump to 1:36

This topic is being discussed because I was in my shower the other day, which is where I do all my best mental wanderings, and I thought that the phrase “design better” could be taken in two very different ways depending on your state of mind. “Design Better” could be an inditing statement that suggests that some particular design is not all that id SHOULD be and another way to interpret that sentence is that someone feels up to the challenge – as in “I Design Better” or “We Design Better” … I could see this as a slogan.

But what does this actually mean? I think we need to break the two words down before we get into the bigger conversation.

What does “Design” mean to you? What does “Better” mean? This is really the tricky part since “better” in the AEC industry could mean a whole bunch of things, including gradations between similar items. For example, better for a developer might mean more profitable. Better for a municipality might be a higher percentage of stone, for an owner, it might be a shorter construction schedule.

So what does “Design Better” mean to me? a reflection of the creative process that yields an actionable result. When I design something, there is an idea, I can articulate it. The end result turns into something that I can hold or look at and it serves a purpose. Design is a verb because it suggests that there is a process involved.

Bob Borson – Design Origin story jump to 6:05

I think in order to get into this conversation, I am going to do the one thing that I typically hate – I am going to tell you my architectural origin story in an effort to get you into my head space.

My design process is a direct result of my career trajectory – both the good and the poorly planned. I worked on interior architecture projects for the first several years and keeping water out of a building was not on my radar. The contractors that I generally worked with were spectacularly talented. There is a lot of money in play where retail is considered – frequently the leasing terms the retailers get is a certain amount of time of free rent, time normally spent building out the space. Savvy retailers will The level of retail rollout projects I worked on would pay a premium for highly skilled and organized contractors because their ability to get the project built correctly ahead of schedule meant they could open for business and not be paying rent. There were rarely issues and those contractors looked after the project like it was their firstborn child.

At any rate, once I started to really feel like a loser because I wasn’t licensed yet, I decided that I wasn’t prepared to take the test because I didn’t actually know how to be an architect. The projects were not technically difficult and the contractors made sure nothing went wrong … so I changed jobs to learn how to detail buildings, which still didn’t happen because everywhere I went, I was quickly moved into a design position and put in the room with clients because these were the things that I was naturally predisposed to doing well – at least better than the other things. So eventually, frequently quickly, I would change jobs again so that I could go somewhere and learn how to keep water out of buildings. This is actually what brought me to doing residential work because I figured that I would get to work on all the various aspects of a project out of necessity and I would absolutely learn how to detail a building … and that actually worked.

Are you still with me?

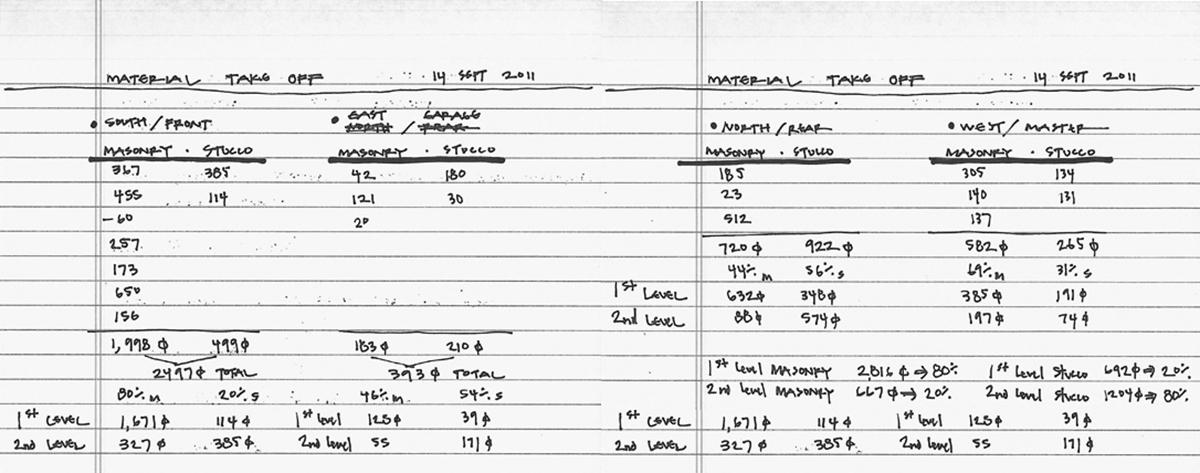

Okay, so I was obsessed with learning how to detail things and everything I drew became an exercise in how it was built. We were working in AutoCAD and I can tell you that I drew a line for every surface that existed in a wall assembly. I would literally draw a line for the inside face of a wall, then offset that 5/8” for the gyp board, then 5 ½” for the exterior studs, and then another 5 ½” for the brick ledge, then work my way back towards the interior 3 5/8” for the brick, followed by then offsetting the line I drew for the exterior side of the stud 7/16” for the OSB sheathing. If you were keeping up, that is 6 lines for an 11 5/8” masonry wall.

Okay, so that’s enough of all that, but let’s just say this manner of thinking continued for the next 15 years and I am now unable to look at walls without adding in this “assembly” mentality. When I am driving down the road looking at buildings – doesn’t matter what kind of projects – I will evaluate them based on how they are put together.

All of this is why “Design Better” means that we need to be looking at our projects as an assembly of their parts and how they are put together. Furthermore, this is not just an architectural consideration, it applies to developers, builders, municipalities – anyone who has a role within the built environment.

Andrew’s Idea of Better jump to 14:01

So this was a tough task for me. I’m not sure how to define “Better”. In the episode, I definitely struggle. I think that a few years ago I would have been able to answer this question more firmly. When I was running my practice and knee-deep in all kinds of projects I think I might have had a solid answer. That answer would have probably revolved around budgets, efficiency, energy, clients, and users. In the episode, I talk about attempting to address all of the different aspects involved in a project. The goal of “Better” is to address all of the issues and elements of a project from the grand gesture down to the small details. The goal is to ensure that all of those have a responsibility to all the elements of a project like climate, budget, regulations, clients, location, context, culture, constructability, social, and so on. I think that is a good way to seek “Better”.

But now with about a week or so to think about it, I may have altered that notion a smidge. I think that “Better” is a notion that should always be evolving for each of us. It should always be at least one step ahead of where we are now. If you set your goals today for better and in the future you meet them all, your definition for better needs to change. It should be a continual cycle for Better. Because in my opinion, when it comes to Better there really is no finish line. Because we can always do better and we should all strive for Better every day. It may not always be possible, and at times I know it can be extremely difficult, but we should still pursue our individual definition of “Better”.

Actual Design Considerations jump to 16:18

There are considerations that are an integral part of the design process to should be anticipated and built into the process

Designing to the ability of the contractor – thinking about how something is built, the sequence and order in which the design will be built, the availability of the materials, etc. This is not a statement against the skillset of the contractor, but if you are designing a building that uses materials that have to get shipped in from another part of the country, maybe some additional considerations should be added to your to-do list.

Budget Considerations – I might get myself in trouble with this one but I think that architects have some responsibility to consider the actual budget they are provided. While I don’t think that we alone have this responsibility, it certainly should be something that is helping to drive decisions and solutions that we provide our clients. I can tell you that I am constantly advising my clients on decisions that are made that are driving costs disproportionately within the budget. Since I am a service provider, I have a responsibility to advise and direct, but ultimately the decision rest with the client … but are they knowledgeable enough to make these decisions without guidance?

Material Lead Times and Project Scheduling – This is really a direct extension to the second item on my list, but knowing the order and sequence in which buildings get built should inform the decisions you make – or at least, you should consider these items and with intent make a decision that drives the project schedule.

Understanding Building Materials and their Unit Sizes – This is one of those items that has always jumped out at me when I look at the design decisions of less experienced individuals. Maybe this was born out of my technical development taking place as I was designing and detailing modern houses – who knows – but knowing the size of building materials can fundamentally drive the size and shape of the spaces and buildings that we are designing. Something as simple as knowing that wood studs come in very specific pre-cut lengths and if I want a space to be slightly larger or smaller than these lengths will drive costs and potentially waste a lot of material. Again, it’s a different matter if this happens for purposeful reasons but it definitely shouldn’t happen because somebody simply doesn’t know the size of a wood stud.

Better is Different for Everyone jump to 24:51

There are a lot of invested groups when it comes to the design, construction – and in the case of Planning and Zoning Departments – the actual existence of the buildings we create. We have all had moments in our professional experience when we have to explain to an owner that what they want to happen is unlikely to actually happen due to some prescriptive regulation that defies obvious logic and our ability to rationally explain away. One of the worst “invested groups” that I’ve had to deal with is over-reaching quasi-judicial Planning and Zoning groups that develop design guidelines that are based on prescriptive design requirements like (be ready, this sample list will trigger PTSD for some architects):

- 85% of the façade will be masonry, of which 15% will be in an accent material.

- 4” caliper contributing tree required for every 25’ of frontage.

- Glazing is limited to 22% with reflectivity below this value ___.

- The building must offset at least 10% for every 50’ of building length.

I wrote a post about this process ten years ago in an article titled “Planning and Zoning Departments Make My Face Hurt” and it walks you through some of the specific nuances of what Planning and Zoning Departments require to make an attractive building. However, this is no longer the case for people practicing in Texas. Andrew breaks down the 2019 Texas House Bill 2439 in which the legislature passed a bill that addresses regulations adopted by governmental entities for the building products, materials, or methods used in the construction or renovation of residential or commercial buildings. I can tell you that this is a somewhat divisive bill because some people (like me) are under the impression that the government should not be mandating which building materials I can or can’t use … but for me, this removes an aesthetic control that I do not feel is warranted. The flip side for some is that they feel like it removes a layer of protection on the general public from having cheap and ineffective materials used in our buildings.

What I find so fascinating about this materials debate is that I want to remove prescriptive aesthetic and architectural mandates from the government’s decision-making process. Building cheap and poorly performing buildings isn’t even a consideration for me – but that’s what the people who are against this bill are stating that this is exactly what will happen … which brings us all the way back around to the beginning of our introductory statement of “Design Better”.

Would you rather? jump to 44:18

Today’s question might seem simple and that’s because it is … this also falls into the “there is only one correct answer” variety of questions and if you get it wrong, I don’t think we can hang out together.

Would you rather have super-sensitive taste or super-sensitive hearing?

The answer to this one might be influenced by your definition of how “super” your sensitivity actually might be … but there’s still only one correct answer.

Ep 077: Design Better

This show admittedly has a negative overtone – which was not the intent. My intention with this topic was more of a rallying cry for those of us in this industry to challenge ourselves to be more considerate … with the emphasis on “more” because there are a lot of great architects out there that are “designing better”. I believe that whoever you are, you can always aspire to do better. That is part of the thought process that happens when I look at work and think “Could that be better?” Of course it could be – so what was missing? What happened that kept this project from being all that it could be? There’s got to be something so it will start with me. I can do better.

Cheers,

Life of an Architect would like to thank our media partners Building Design and Construction for their gracious and ongoing support of this podcast. This is the 3rd year of our partnership and we are grateful for the guidance and insight they share with us that helps direct the show.