Architecture is about words as much as images.

Let that sink in for just a moment … I say this after a week of mid-term and project reviews in my department. The reason I say such a thing is quite obvious, to me, but I think for many in school and also in the profession, it is not so simple. I am not attempting to say that I am the most eloquent speaker when it comes to describing my work, ideas or goals. This skill takes time to learn (for some) and typically a fair amount of preparation. Despite the fact that I most often prefer to just “wing-it”, I must confess that I do not think this is how to present my best. Of anything. Ever.

So as I have sat through several dozen presentations so far this week with more to come, (it’s the week before spring break) I can point out the exact moment the students either “intrigued” or “lost” their jury. For the most part, the presenter never notices this occurrence. Or when they do, it is most assuredly too late. I admit that this is probably a difficult item to pinpoint while you are in the moment speaking about your work. But I can guarantee you that it is there and if you were able to watch a video of your presentation, you would also be able to see this moment. I think to a certain extent it is our need as designers to over-explain our work. This may be one of the best times to fulfill one the most infamous of adages in architecture… “Less is More.”

There is a point at which your words about your design begin to work against you. So it is often best, especially in a jury review, to let questions be asked so that you can respond to the inquiries. Now you must still provide and discuss the important aspects of your project, but make a sound attempt to curb yourself and not overspeak. Granted, even in that scenario you can still say the wrong thing and muddle your project in the eyes of the jury. I have seen this happen to first-year students, graduate students, and professionals of many years. No one is beyond this possible misstep in our profession, but your goal should be to lower the possibilities when you speak about your work.

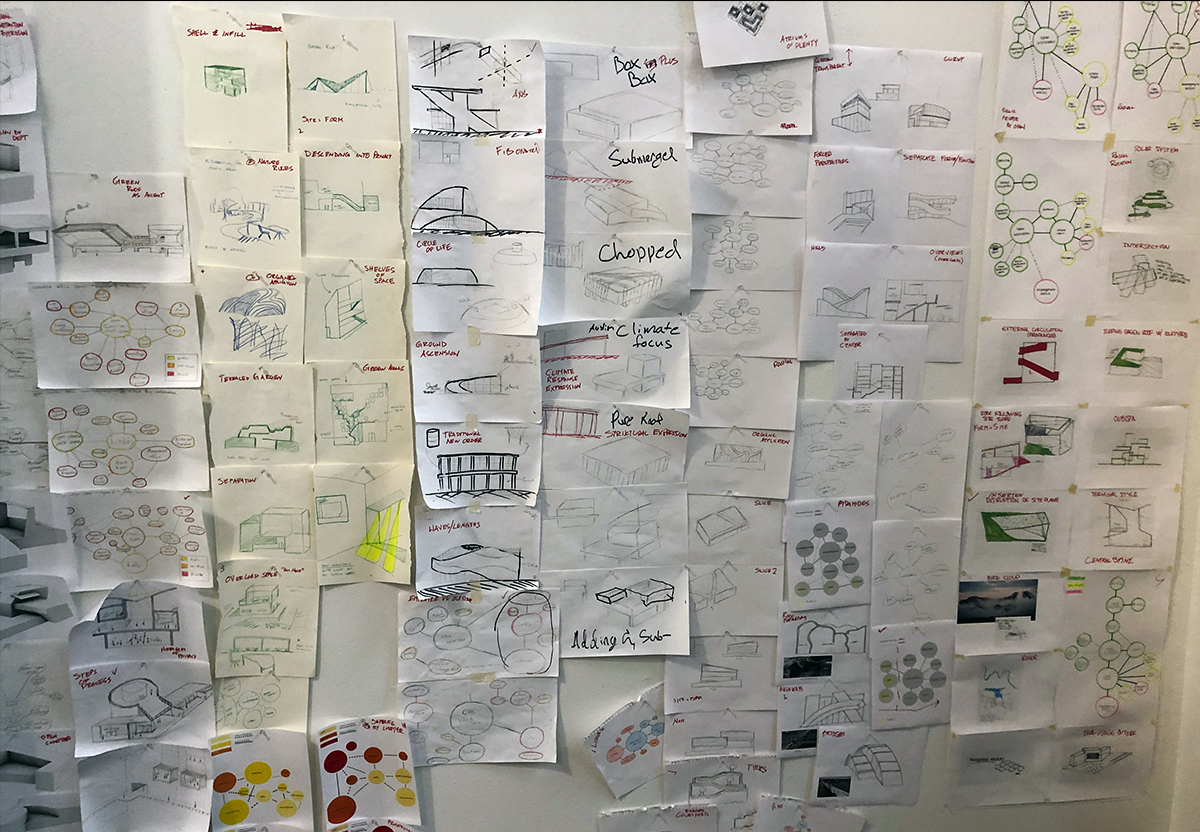

I believe this springs from the trouble with words. They sell your ideas just as much if not more than your images. They should work together and reinforce each other. The words supplement your images and give them meaning. This is where the stumbles begin. How is it best to manage this bit of typical behavior? Well as I seem to repeatedly tell my students, talk about the main singular idea or concept that drives your project. You don’t have one you say? Well, then that is a major problem already. One of my main methods to combat this in my studios is to get my students to select a word, phrase, or sentence to “describe” their project concept or goal. I find that many students struggle with this exercise. In reality, many professionals have the exact same struggles. Many of the most successful architects have the ability to bring an emotional, theoretical or idealistic element to the way they speak about their projects. This is how they convince others to hire them to create those projects. This is an innate skill in some, but it can be a cultivated skill as well.

How do we talk about architecture? It should be not in the sense that you are a tour guide hired by the owner to walk someone through your project.

“On the left, we have the main exhibit area, and just beyond you will find the offices and public restrooms…”

Do you now feel inspired or excited about the new space exploration museum I am designing? (insert any project you think would be the most awesome to design) I exaggerate a bit to prove the point here. What is it about the project that excites you? How can you put that into words? Which of those words have the most powerful meanings? Once you can define that, it should become the mantra of your project. Does this decision inform that idea? Does this spatial arrangement? Materials?

“ This project is about our connection to the universe both known and unknown.”

Is that more interesting? Do you want to know more? I would wager to say that you do. Now I have a vision for the project. How do I attempt to express this concept in form, spatial arrangements, materials, positive and negative, light and dark, seen and unseen? This is a statement about a project that offers multiple opportunities and responses. There is no one right answer. You have the freedom to make this your own. How do you think humans connect to the universe? How can you enhance this connection with your project? Or can you explain it within your project?

To be brutally honest with myself, this is a skill that I have not excelled at in my professional career. But as I have been teaching, this skill is now one that I critically consider all the time. I think about the manner in which I speak about architecture and how to do that with increased clarity. This is not to mean that I now expend more of my words in jargon and archi-talk, but that words are chosen carefully. I feel as though during my attempts to help my students clarify their own thoughts about architecture, I have begun to do the same for my thoughts about architecture. In the end, I strongly believe I will be much better for having done so.

Remember… Architecture is difficult. If it were easy, everyone would do it.

Until next time,