Today we are focusing on drawings and the question that first comes to mind is to talk about what we draw, why we draw it, and who we draw it for and why that impacts all other considerations. With all of that on the table for consideration, the real conversation is centered around how much … and why the answer to that question is complicated … Welcome to EP 143: Architectural Drawings: Excessive or Essential.

[Note: If you are reading this via email, click here to access the on-site audio player]

Podcast: Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn

Why are we now drawing so much – as in, what is driving this? Contractor request? Client desire to create a tighter set of documents for the control of pricing and construction (limit change orders, etc.)? The Architect’s need to control all the nuances of the finished product? This is as much a show complaining about where we find ourselves as any sort of critical discourse on the matter, meaning, I am interested to see where this goes.

What Counts as a Drawing? jump to 3:50

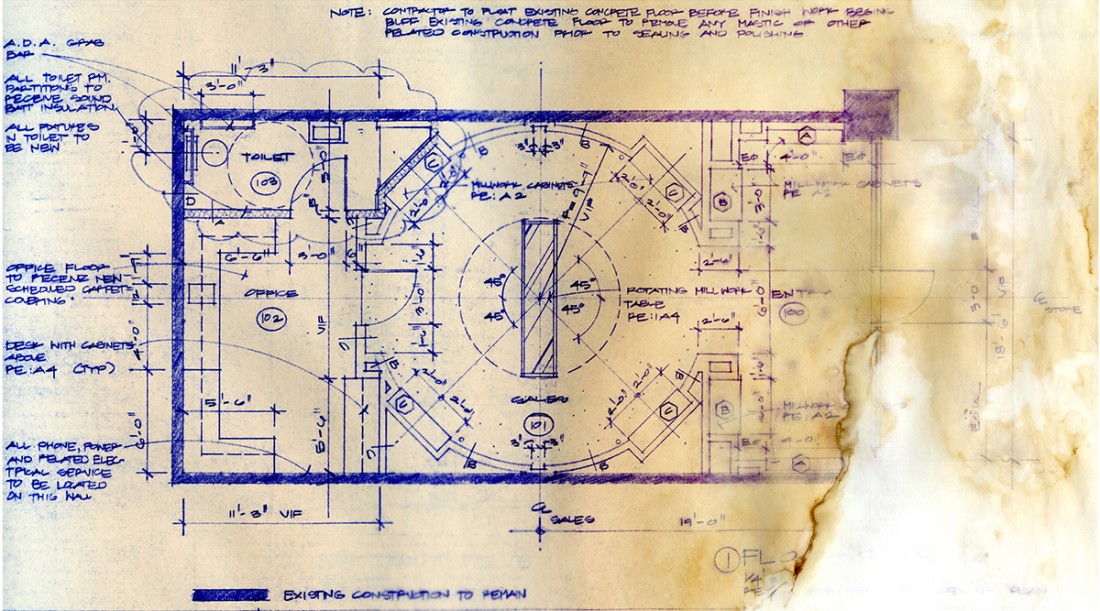

Think about the drawings that are generated from initial concept work through construction -there are different sort of drawings that are generated along the way through each step of SD, DD, CD and CA. At each one of these moments, architects are generally talking to different groups of users and as a result, utilize different styles of drawings as well as documents that contain (or portray) different types of information. The information conveyed to a client, someone who might not be well-versed in readings 2-dimensional drawings, would be completely different that the sort of information conveyed to the contractor or building official reviewing the documents.

Since we have brought up “renderings” (more professionally known as 3D visualizations, we need to discuss the evolution that the role these sorts of communicative drawings has gone through in the last 10 years. These 3d visualization tools that have become an expected part of the delivery process – at least in my world. I made it through +/- 20 years of my professional career without really needing to rely in any meaningful capacity on producing these sorts of drawings but I can’t imagine doing a project without using them now. They are predominantly used during the initial design phases of a project and have brought real value to the process – especially on the client side of the process.

I would love to know if someone else is experiencing something different.

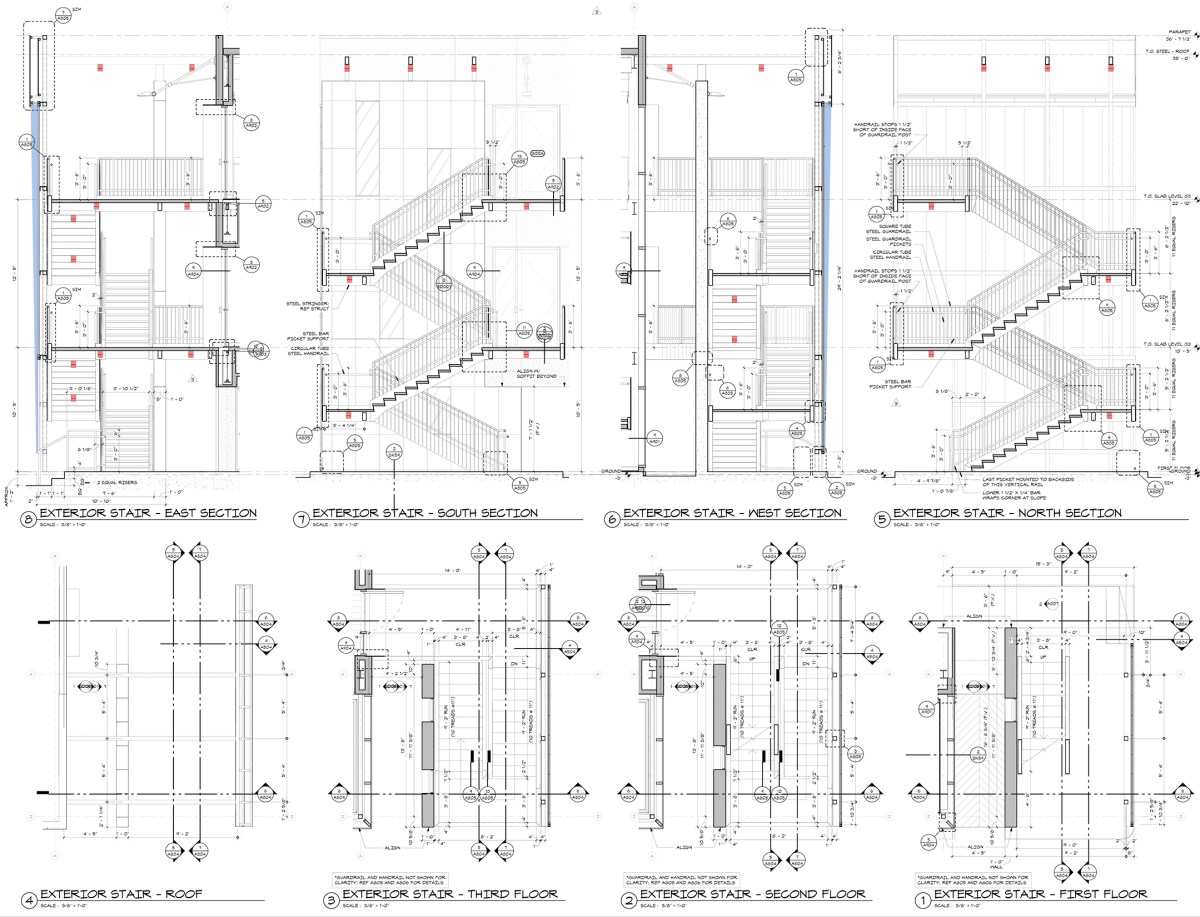

Andrew and I spent a little bit of time talking about the evolution from Hand Drafting to 2D drafting Software to BIM and how the ease at which drawings can now be created, construction document sets are becoming more and more drawing intensive. I’m not entirely convinced this is a good thing but now that we the ability to model our projects 3-dimensionally, we have the ability to create as many section, plans, elevations, etc. that we want. We have found ourselves in the position of having to consider the value of “just because I can, does that mean I should?” when it comes to the depth and breadth of documentation that provides value.

Client Requests jump to 10:42

We don’t really feel that clients are the user group that are driving the amount of documentation that we are preparing. There is the possibility that clients are looking to have a more thorough set of architectural drawings so that they can have some assurances on the accuracy and completeness of the pricing they will be getting from the contractor, which seems to be a completely reasonable position in which to put yourself. The specifics of this position are generally not mandated by the client, it’s normally a direction to prepare as complete a set of documents as possible (or reasonable … which is a different sort of slippery slope) so that change orders are minimized and a certain financial comfort level is obtained.

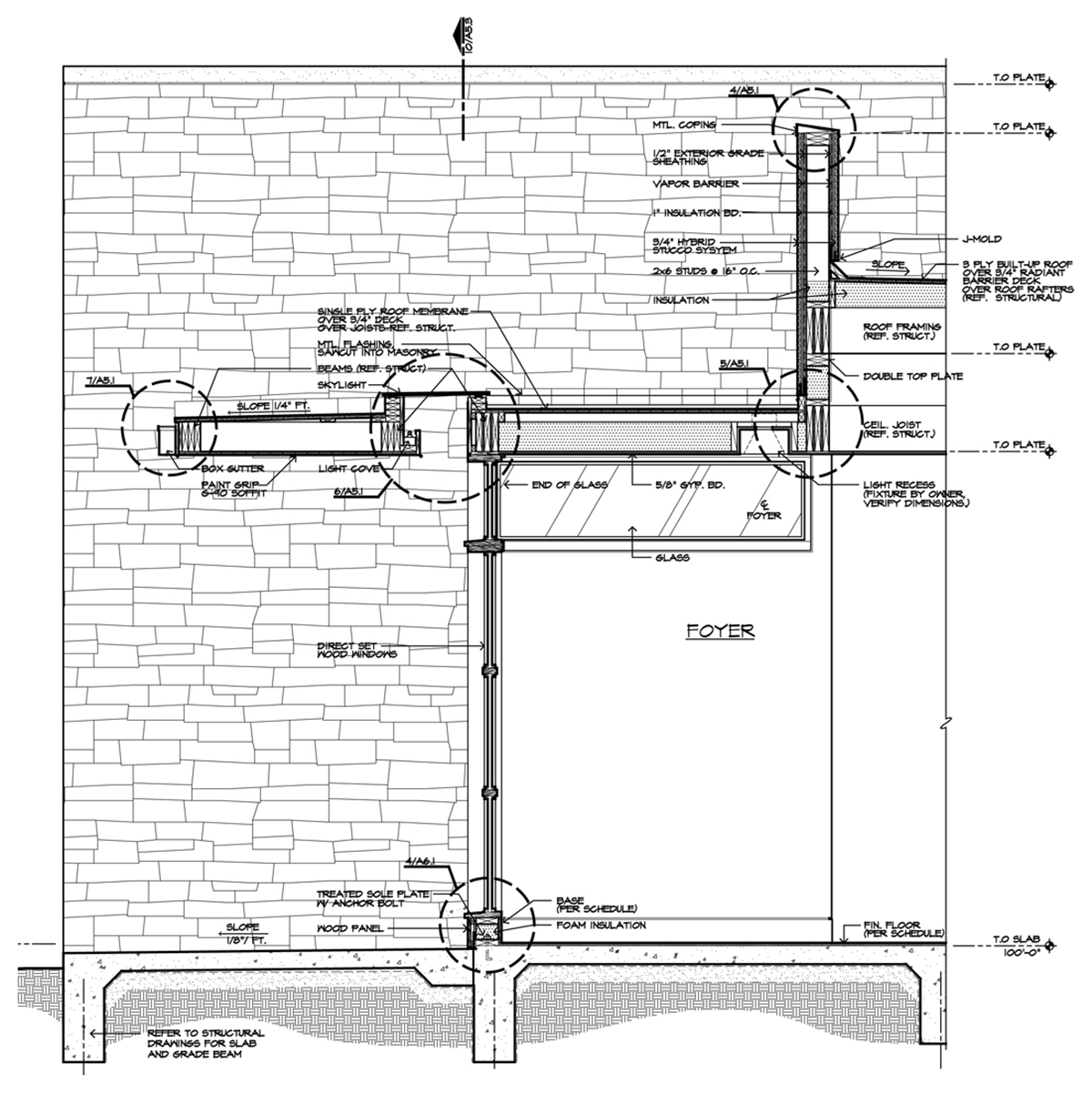

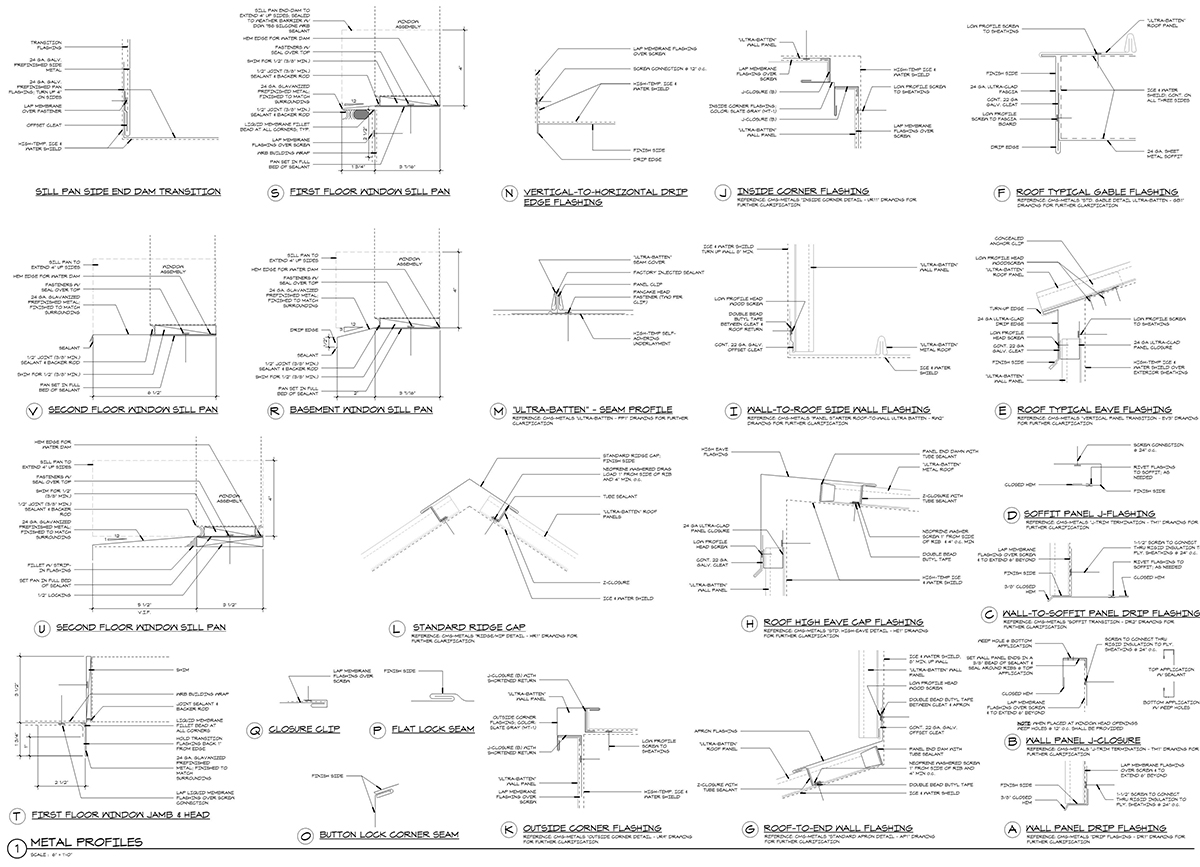

Part of our conversation covered how pricing might actually be generated by the contractor – cost per square foot based on experience of working on projects of similar sized and complexity. This clearly has some value during the very initial stages of the project when there are a lot of unknowns in place but things start getting rocky when information is provided in the documents and is either missed or overlooked by the contractor. There is a story that is shared (which is why I am sharing the particular image shown for this section) about a remote project I did a few years back where the owner asked us to document the project to an extremely high-level because a) they wanted an acceptable level of financial accuracy to the pricing, and b) the contractor wasn’t familiar with building this sort of project and we (the architect and owner) wanted things done a particular way. The example provided was the flashing details we prepared that very closely matched the manufacturer’s standard details for the installation of a metal roof … so we draw all of them. In the end, there wasn’t much evidence to support that the contractor even looked at these details based on the issues that we still had to address.

Contractor Request? jump to 18:00

This section is where we spent the majority of our time, not a surprise really since the majority of the time spent creating architectural drawings falls in the construction documentation phase of the project. Very quickly we agreed that contractors aren’t asking architects to prepare more drawings, we are doing it ourselves. While there is a case to be made that this decision of ours is reactionary, there is definitely a difference in the amount of documents produced based on the contractor we are working with the build the project. Meaning, the best contractor I have ever worked with required the least amount of drawings. Surprising? Anyone who is in this business would not be surprised by that comment. This is an interesting bit of the discussion because I would answer this question differently based on if I am doing commercial work versus residential work.

Punished for drawing too much – did you know that was a thing? The project that I did down in San Antonio, Texas was a great example of the contractor either deciding to just provide square foot pricing based on how they typically did things, or ignoring the drawings because they weren’t used to going through architectural drawings. Seems crazy, right? This was a project that came in over budget by a fairly significant portion – maybe 30%. Since I don’t normally have this problem, I spent an entire day with the contractor going through there estimate and if we looked at 400 things, 390 of them had something wrong, not thought through, or just ignored outright … and it definitely wasn’t because the information wasn’t in the drawings

Here is another fun consideration – and it’s the exact opposite of drawing too much – it’s being punished for drawing too little – even in the little tile renovation in my house, people (meaning tile contractors) called me psychopath for the level of specificity I was looking for – which I refer to as “alignment”. The article I wrote was cleverly titled “Motherflipping Tile Joints” and it is a painstaking step-by-step walkthrough of why I did what I did, the thought that went into the process, and how in the end, there were still issues.

This is a moving target and there is no right answer – especially if you work across a broad spectrum of project types and market sectors. The examples listed above were for residential projects, which are both simpler and more complex at the same time. Easier to have a conversation most of the time and get to a reasonable conclusion, but lack of process and paperwork make some builds a lot more challenging.

In commercial work, the things that contractors are able to do with barely any information at all is rather remarkable. The amount of documentation they ask for is shockingly low (especially if I compare it to a residential project when the construction cost and square footage cost are scaled up to similar levels). Most of the time, it is the architect making a determination on what will be needed to curtail the amounts of questions being asked during construction. Nobody wants to receive a thousand RFI’s (Request for Information). There is also a huge consideration to limit the amount of Change Orders for work/scope being left out or not articulated with clear intent and direction.

Hypothetical jump to 48:40

I have to be honest and confess that I prefer discussing these hypothetical questions to most as it requires you to think through preposterous scenarios while pushing on some boundaries of how you view not only your surroundings, but possibly your own shortcomings or biases. I will also confess that I tend to continue to think about my answers to these situations long after Andrew and I are done discussing them. Sometimes you realized that you missed some obvious consideration or opportunity and that could possibly alter how you would respond to the question.

Could you give up electricity for $100,000 a month? You have to go at least 6 months before receiving any payout.

You don’t have to listen to this one as the answer for anyone should be “yes” because $100,000 a month is a LOT of money. I dropped this amount down during our discussion as I thought this value was set so high as to make this an easy deliberation. Once the amount was set, this really turns into a question about lifestyle and how you would function without electricity. Once you remove financial stress as a point of stress or concern, you don’t even really need a job anymore unless you are concerned about staving off boredom, what does your daily existence look like?

At the 54:40 mark I mentioned an Instagram account that I follow that belongs to Mark Hogben, a gentleman who is a off-grid wilderness bushman who is living with Parkinson’s disease.

EP 143: Architectural Drawings: Excessive or Essential

So after all this talking (or reading/listening in your case) where did we land? No where quite honestly, and I think that depending on who you ask, you will get different answers 100% of the time. I generally fall in the camp of drawing more, but not because anyone specifically asked for it, I think drawing more reflects a more complete and thought through problem-solving process. As a result, I feel like I have more options on how to solve a challenge because the chances that I’ve come across it while drawing, as opposed to looking at something in the field, is just a better way to go. My party line on this topic is this:

I will err on the side of being over-prepared and deal with the consequences because the other options seem far worse.

Cheers,