After a week full of various studio reviews, I have realized how essential diagrams are to the presentation of one’s architectural ideas. While they may not hold a large place within the practice of architecture, they are certainly critical to success in the process of architectural education.

So I typically make all of my students at every level create some type of diagrams during the semester. The intent of these varies by year level, but I still require them. As I sat through multiple reviews this past week, only one of which was my own studio, I was almost slapped in the face by the overall lack of diagramming that is occurring. This may be specific to my school of architecture, as I do not yet participate in other studio reviews at other universities, so I cannot claim this to be a substantial systemic lacking. But I can simply say that it is crucial to the educational presentation of ideas and projects. Diagrams can be complex or straightforward, 2-Dimensional, 3-Dimensional, or anywhere in between. For me, the main goal of any diagram is to provide the most crucial information about the content quickly.

Diagrams for Conceptual Ideas

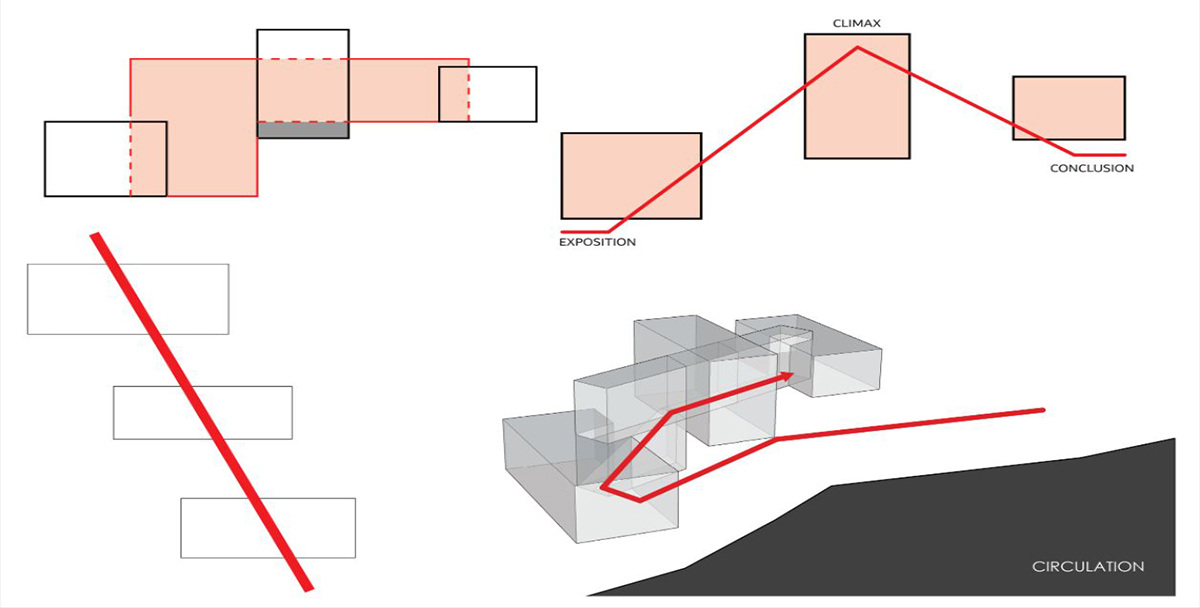

As architects, we are visual people. We want to see things, and that is often how we best understand them. So if the words are the only method being used to convey the project concepts, it is often difficult to determine the desired outcome. Conceptual diagrams help someone else understand the intentions and design ideas. They can be concrete and direct or also extremely abstract and fluid. This is when diagrams are essential to understand the proposed project properly. If a reviewer has to imagine the project in their mind, then the proposal has already “failed,” so to speak. By this, I simply mean that the ideas should be visible. What a student imagines in their mind versus what another person imagines will be most likely different. So therefore, for the sake of clarity, it needs to be shown. This can also be applied to the world of practice when we speak about clients. Often it is a miscommunication of ideas that can cause trouble in the design process. Showing the best representation of your conceptual ideas is critical to success. These types of diagrams can vary widely, but they are usually simple in their nature and are not always an indication of the final proposed work.

Diagrams for Spatial Relationships

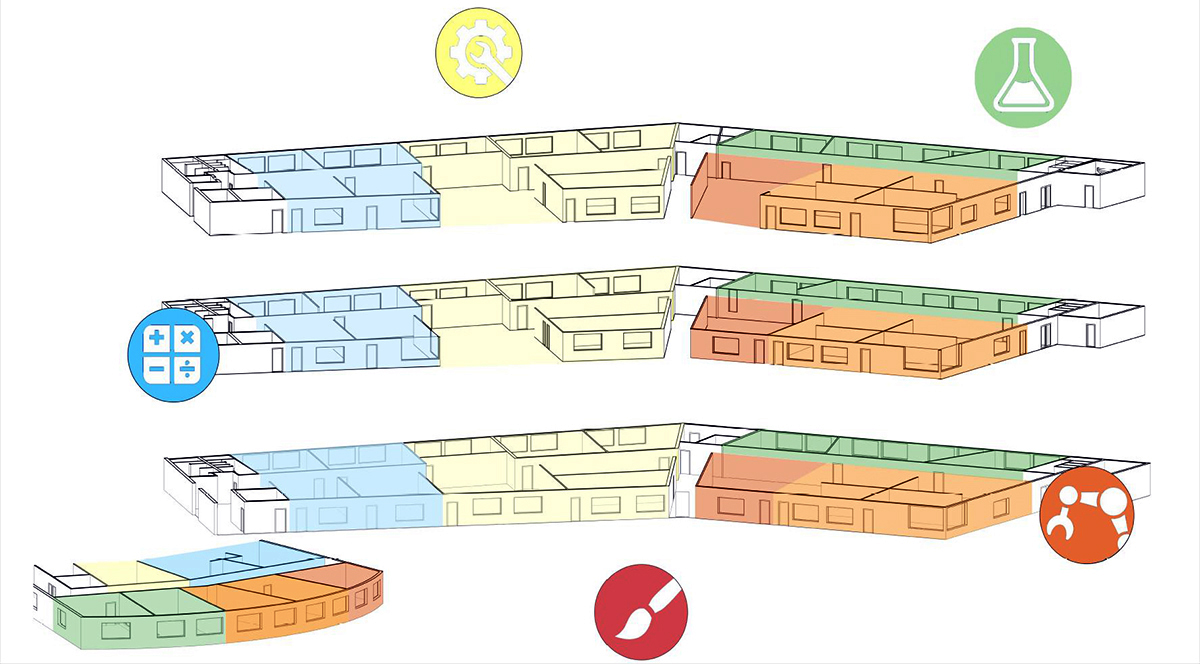

These are applied once the project is near or at completion. This means they help explain the proposed project in some way. They can be programmatic, safety, circulation, volumetric, or any other type of spatially oriented diagram. They provide information about the various “things” that will happen in the project. It could be about proposed activities or give some ideas about usage schedules or the flow of the masses. The thing about these diagrams is that they are typically based on the final proposed work. So they are created over floor plans or sections of the project. They can be simplified or highly detailed. I tend to prefer simplified diagrams as my goal for any diagram is to convey the information as quickly as possible. So one creates these types of diagrams after there is a solution. Of course, these should be layers of information that have been in the project solution all along, but this is the opportunity to convey them succinctly while also thoroughly enough to prove the point.

Diagrams for Technical Intent

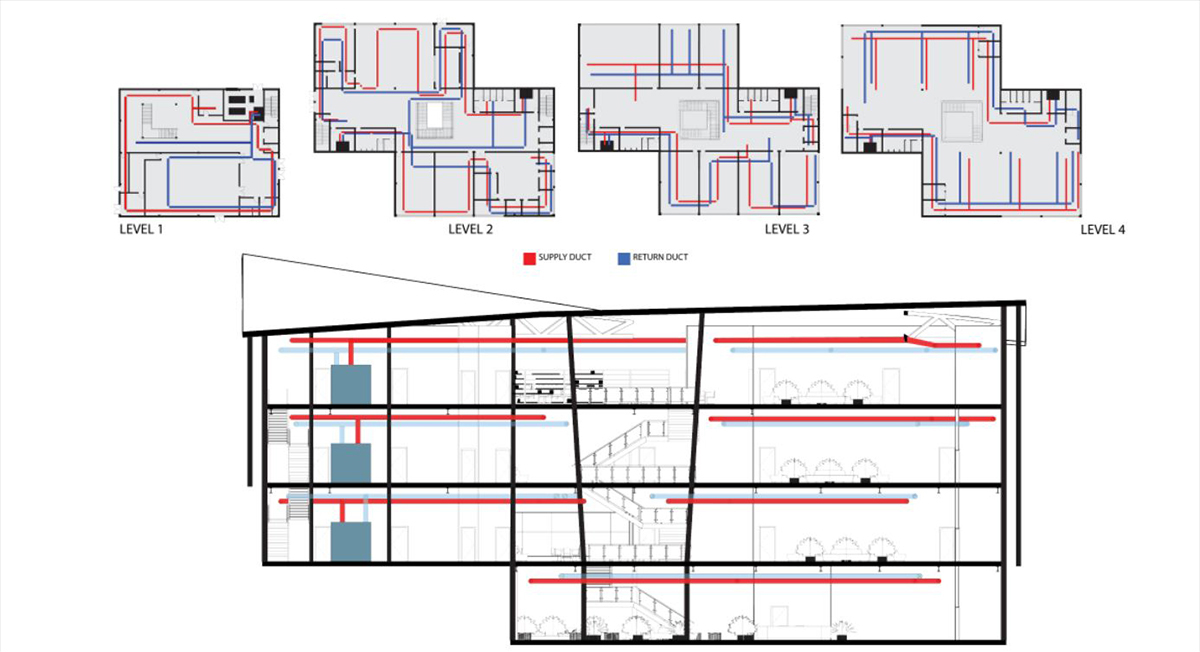

This last set is mainly about conveying possibly highly technical information in a simplified manner. Sometimes a student’s project may have several very technical details that have been explored and even designed on some level, but it is only spoken about during the verbal presentation. This is a mistake that can be simply corrected with proper diagrams. For example, a simple diagram could support complex HVAC systems or sustainable practices that a student may have proposed for their project that never shows up in any plan, render, section, or drawing. It is not challenging to diagram a proposed cross-ventilation process over a simplified section. This may be a more effective image than some overly technical section and systems drawing. But it will definitely be more effective than words describing this system.

I know there is not always a direct correlation between the academic studio and the practice of the “real world.” However, I still believe that creating diagrams is an important skill for an architect. It is a skill to be honed during school and then applied once in practice in various ways. The ability to quickly convey information and thoughts visually has, in my opinion, never been more valuable than in today’s society. We live in a world of short attention spans and catchy imagery. Those should be the goal for any diagram; to grab the attention and to explain content quickly. While I can agree that portions of professional practice do not benefit from diagrams, and our work requires a much more technical conveyance of information, I still believe that diagrams are a helpful tool for any architect at some point in the process.

Until next time,

This is another entry into the ongoing Studio Lessons 101 Series.

Starting Architecture School

Architecture is about Words

Architectural Resolution

Architectural Precedents

Architecture Student Tool Kit