How much drafting does a fully licensed architect do? What is something you learned in the industry that you hadn’t been taught in school? Are you as condescending to your employees as your redlines let on? All this and potentially other hateful questions on today’s episode as Andrew and I answer discuss the questions submitted by the listeners. Welcome to episode 108: Ask the Show – Fall Edition.

[Note: If you are reading this via email, click here to access the on-site audio player]

Podcast: Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn

Today’s show consists of questions that were submitted through my Instagram account – well, technically speaking, I asked people to submit questions, and we choose about 10 or so interesting ones that we thought we could effectively handle when only allotting ourselves about 5 minutes to answer. If you submitted a question and we didn’t answer it here, it’s probably because your question is either a topic that we plan on really focusing on in a later episode, was too complicated and specific to you that nobody else would really be invested in the answer, or it didn’t make sense – mostly because it wasn’t in the form of an actual question. In addition, we keep questions that were submitted for previous Ask the Show episodes and consider them as well – so some of these questions date back to episode 64.

Should we be more realistic about true practice in school or keep up the romantic ideals? jump to 3:13

Question submitted by @allisonharris – Allison Harris

Bob: If I can only choose between these two options, I would choose romantic ideals – mostly because I believe that you go to school to learn how to learn and for architects, this manifests itself in critical thinking. I know that is not the point of Allison’s question – it most likely has to do with making sure that architecture students come out of school equipped with the knowledge they need to not only be successful but to contribute in a meaningful way.

For most of the roles that are possible, as far as careers in architecture go, most people do not go into school, nor do they come out of school with any real understanding of what those roles are or the part they play in the process. Andrew and I spent some time talking about the educational process and debating the merits of having the first year of an architectural education be more of a primer that introduces architecture students to the entire gamut of what traditionally exists in our industry. This might then allow students to choose a more focused path while in undergraduate school that allows them to zero in on the things that suit their interests and skill sets rather than potentially preparing them to perform a role that they are not suited to perform.

Andrew: I think there needs to be a precise balance between the two options. After a few years in academia, I have changed my thoughts on this question, and they continue to evolve. I think the issue is that most schools seem to push to one option or the other when in my opinion, the sweet spot is in the middle ground. Architecture school is about learning how to think about architecture in a way that involves a process of critical evaluation and thought. That is a skill that you will utilize for the rest of your life in the profession. Yet, there is not enough information provided about the actual work that happens within the profession. I think some of this is just academia. Many of your professors, to be bluntly honest, may not know how the profession operates currently. Many have either been out of practice for many years or some never were in the practice at all. So the push to insert more of the “profession” into the curriculum is not always easy or possible.

I hate to ride the middle ground here, but in reality, you need to learn the process of creating and thinking about architecture and also be made aware of the possibilities and operations of the practice. It is not an easy balance. I am still trying to find that balance in all the studios I teach. Again, part of your architectural education is meant to happen while working. Now this may not be the best model any longer, but that is still how the process works. (I could talk about that for much longer)

Should architecture students go through all 6 years at once, or do 4 and then work for a few years to gain experience and then go for their masters? jump to 9:39

Question submitted by Colin Balbach [private account]

Andrew: I think the best answer is “No.” There are many reasons to put some time between the 4-year undergrad and the 2-year master’s if that is your path. Now, of course, not everyone has to take that path, but if you are already in it, then you should consider putting some time between them. I think the greatest benefit here is to go out and work in the industry for a few years to possibly discover your passion or areas of interest. This will then, in turn, make you more focused during your graduate school tenure. I think you may not have enough knowledge about the profession when you complete your undergraduate degree that the exposure to all the various positions, specializations, and interests in the field.

The real trick here is not to stay too long. The longer you stay in the workforce and collect paychecks and gain responsibility, the more difficult it becomes to step away. So set yourself a plan and try your best to stick to it. The other benefit is that you can possibly save up some money to pay for the graduate degree. I know in the current economy that may be tough, but it is a possibility.

Bob: The reason I think there is some value to putting a break between getting your undergraduate and graduate degrees is that it provides you the opportunity to learn a bit more about who you are, where your interests lie, and what you are actually good at doing. This information can then be used to direct you towards a graduate degree program that possibly specializes in those things. Generally speaking, I am not a huge fan of people getting their undergrad and graduate degrees from the same place. I would much rather see someone branch out and get exposed to different ways of thinking as part of their educational process.

What key thing do you look for in potential new hires? jump to 12:22

Question submitted by Mohammed Diallo

Bob: I have answered this question in one form or another several times here on the site but I will try and give a more consolidated answer. I have already looked at your portfolio, read your resume and cover letter – these are the things that got you in the room for an interview. When I am sitting across the table from a potential new hire, at this point I am evaluating their in-person real-time communication skills. What words do they use, do they ask questions, and how engaged are they in the conversation (things like eye contact and body posture)? These are the things that let me know about general intelligence and how you might fit into the culture of the office … with these items covered, I feel like I can teach the rest of whatever isn’t currently in place.

Andrew: I think that communication is very important, as Bob has mentioned. Also, it is about attitude and how a person handles themselves during the interview. The other thing I always looked for was a sense of eagerness and excitement. Do you really want this job? Are you here because you want to be here? Lastly, in a small office, I really need to have a sense that you will fit into the office “vibe” or culture. There is a little bit about the elements that you have written in your cover letter or portfolio. The ability to write is important as you will be doing this to communicate with all the various people involved in projects.

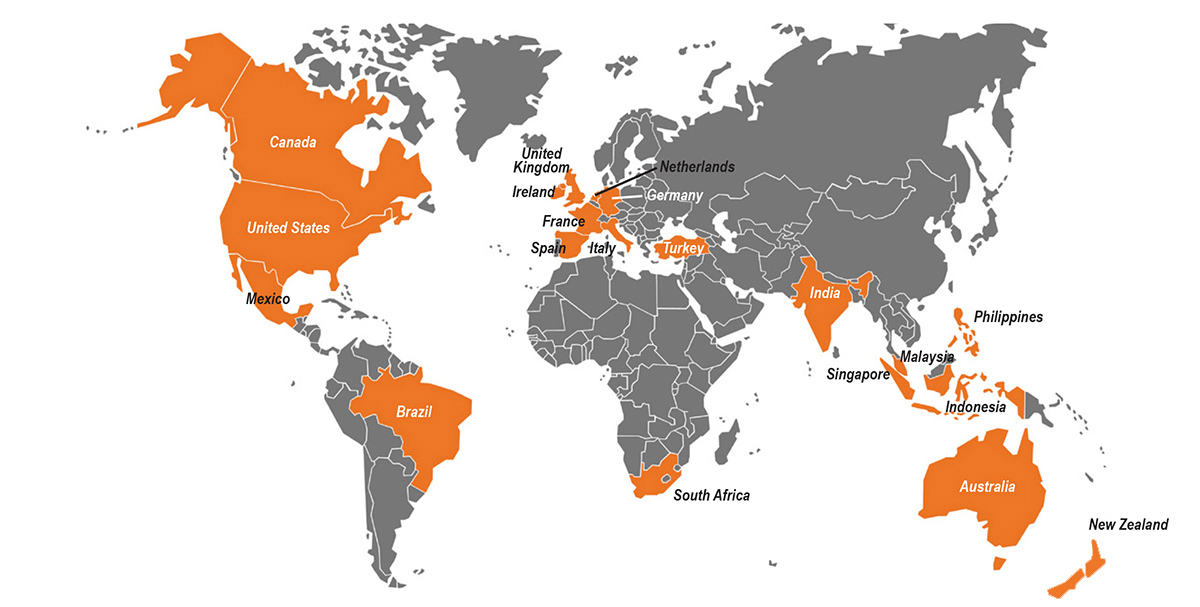

How can a sole practitioner expand their geographic reach? jump to 17:01

Question submitted by @n3architecture – Chris Novelli

Bob: This question has been submitted a few times so we are finally going to take a crack at it. I will concede that my initial reaction to this question is “Why as a sole practitioner do you need to find work outside of your geographic area?” but there are a few reasonable answers to that question. Also, doing work remotely is harder than doing work that is not remote, and whenever I get hired to work in other areas, at least one of two things is present to make that viable.

- As an architect in Dallas, Texas, my fees are lower than the architects in whatever market I am being retained and as a result, the additional expense of traveling for the necessary face-to-face meetings or job site visits still does not exclude me as a potential service provider.

- The client isn’t local to wherever the project is located meaning that some level of travel is required by the architect regardless of where that person sets up their shop.

The answer to this question really resides in how far is the reach you are seeking. The process of getting work in other locations can be as direct as getting involved in the community and growing your network in the area you wish to expand. If the reach is further, most of the people I know do it through social media channels and by creating digital content that allows people in the areas you wish to work to find you. This process is tedious and takes a fairly long time to develop so it can not be your main strategy for developing work.

Andrew: As a small practitioner, I understand that in many instances, your local area may not be enough work to support your office, so there is a real need to move outside your locality. The best answer I can offer here is to network. That is the simplest response. That most likely means growing your network through multiple channels into the new area you want to work in. So that may be through non-profits, volunteerism, contractors, or even other architects. The best approach that I could offer would be to become visible in that new geographic area in some way. You may be surprised at the various methods that you can get involved and make your network grow. I know that other architects may seem like an odd fit, but sometimes that is one of the best ways to get work. One of the most important things to stress here is … while this is the simplest solution, it is by no means the easiest. Growing your network is difficult and possibly the most difficult task you have as an owner. So realize it will take lots of time and patience before there is any payoff.

What are the significant differences in workflow between public architecture and private residential work? jump to 29:54

Question submitted by -Removed Account-

Bob: There are a lot of different directions we could take this answer but I am going to focus in on the thing that came to mind first – which is client experience and knowledge. For the most part, most clients hiring architects to provide public (or commercial) work have gone through this process before and they bring a fairly high level of experience to the process. On residential projects, it is typical that the clients have never gone through this process before and need to be educated and walked through every step of the process. This all comes down to your ability to communicate with people and having spent part of my career working in both of these silos, it is a different skill set to effectively communicate with residential clients simply because so much of that conversation is educational in its nature. Teaching someone why certain things are happening is not the same thing as simply communicating what is happening.

We also spent some time discussing the complexity of these different types of projects and typically how many consultants are brought aboard as part of the delivery process. Most residential projects might have one or two additional consultants whereas commercial projects typically have at least four and that number could be substantially higher.

Andrew: The first thing that pops into my mind for this question is “handholding.” You have to provide much more attention to residential clients than you do for most commercial and public clients. While many commercial and public clients may not know the process, the amount of expected attention is different. Commercial/public clients have their own issues to deal with as part of the work. So they tend to want a little less time. They may still need education about the process, but they do not require so much undivided attention.

Also, the numbers are much larger. In public/commercial work, there is a greater number of persons involved in all of that project. There may be a client committee or a group of stakeholders. There are almost always more consultants involved in the project. Then there may be a larger amount of the construction team, even just the ones that you deal with; jobsite superintendent, project manager, project estimator, etc… So the number of people you manage increases by multiples when the project is public or commercial.

What is something you learned in the industry that you hadn’t been taught in school? jump to 33:25

Question submitted by Mohammed Diallo

Bob: Simple … Communication.

I don’t recall having any sort of formal education while I was in school when it comes to communication skills. I am not simply talking about word choice and sentence structure, I am mostly focusing here on the ability to understand what is really being said in a conversation as opposed to focusing on the words coming out of someone’s mouth. Some people refer to this as gauging the temperature of the room, others might call it reading between the lines. Effective communication skills really reside in your ability to what is really being said when it actually isn’t being said at all.

There are other areas where you need to speak aspirationally to your client (especially true since we are in the business of dream fulfillment) so being able to say yes to something while protecting them from themselves, and still be aspirational about it and get people excited and galvanized behind this vision that exists.

Andrew: When it comes to communication, I think that the real issue is that you do not spend enough time in school talking to people who know very little about architecture. You spend lots of time speaking to others who know architecture ( your classmate, professors, juries, etc.) but most likely none to the average person who will end up being your client.

For me, the biggest thing that you learn in architecture practice is that architecture is about the management of multiple layers of information. You spend very little time doing design for projects. Most of your time on projects is spent managing the project in various ways. This means management of budgets, materials, clients, consultants, users, inspectors, regulations, and on and on. So the skill of management is one that you do not get taught enough in school that you will definitely need to learn quickly in practice. I personally think that being a good manager of all of these layers is what impacts your success the most.

Are you as condescending to your employees as your redlines let on? jump to 39:06

Question submitted by @lester_matos14 – Lester Matos

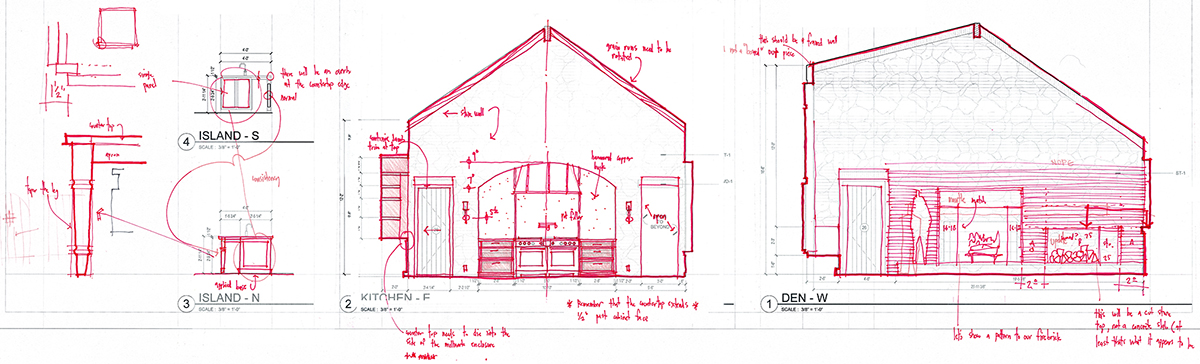

Bob: Not going to lie, I get this question almost every time I show “redlines” drawings I create on social media … and it stings a little every time. I have written about my redlining process several times but it does nothing to put these sorts of questions to rest. I tried to address the perceived “hazing” aspect that seems to come across in these drawings in the post “Architectural Redlines During the Design” but I have to concede that not everyone is familiar with the complete library of posts I have written on this site.

So here’s the setup – I sent the following email to a few people I work with and posed the question to them on my redlines and how they are perceived:

“As someone who has been on the receiving end of my redlines, would you take a few minutes and give your take on this question? I would like you to be as honest as possible – either way, it benefits me so I am not motivated to have you tell me what you think I want to hear.”

I got two responses and I am including them here in their entirety without any editing:

I don’t see how redlines in themselves can be condescending (well… unless you write something like “this isn’t how brick courses, you dumb !?*$.” That would be a condescending redline.

What could potentially make someone perceive redlines as condescending is the attitude of the individual behind them, and their willingness to explain the comments when asked. But of all the employers I’ve ever worked for, you are the most willing to explain the redlines you make. If asked, you always take the time to expand. I promise you that everyone who works with you notices and appreciates that. I know if I have a question about one of his markups, he is willing to explain it.

The second response:

In the context of our very small project teams, often just Bob and myself, Bob’s redlines are more about making me/us think rather than being condescending for the sake of being condescending. Often it might be something that he can tell did not get enough love or attention; something that needs more study. The other thing to note about Bob’s process is that he does not simply plop a stack of redlines onto our desks, he will set aside a bit of time, after hours if we need it, and go through the redlines together to make sure the messages are being captured and that his comments are understood. There is no trying to figure out what he meant by a comment, he explains it in detail and makes sure we understand what he wants to see before we walk away. If you know Bob, you know he would never leave a rude redline directed at someone. Who would that benefit?

I promise you that I am not a jerk when it comes to my redlines – my goal is exactly the opposite. I want to get people to understand why I am doing what I’m doing so that they are empowered to make decisions in the future because they understand why we do what we do.

Andrew: I think that redlines in themselves are not mean. I think their delivery and explanation of them are critical to their interpretation. I love to redline! Just kidding. But I do see it as a useful tool for learning. I also think it is essential to explain the comments to the person that will be making the corrections. Redlines are just the beginning of a conversation about the work. I would never just dump a set of redlines on someone’s desk and walk away. Well, if they have worked for me for quite a while, I might be able to do that because they understand the meaning of my notes, and we have discussed similar redlines in the past. But I am always available and willing to discuss any issues that I make note of on the redlines.

Most of the time, my redlines are more conversational. Did you think about this? Why is this happening here and not there? What was the thought process on this detail? Yes, of course, there is the basic “missing notations” or “this line is incorrect,” but those are usually less of the red on a sheet. They are a tool for learning and discussion. They are not punitive devices for torture.

How much drafting does a fully licensed architect do? jump to 46:25

Question submitted by @saturn_ev – Evan Ortega

Bob: It depends on what their job is. I do almost no drafting at all but there are people at my level in my office who draft all the time. While I don’t think it is the best use of my time, for some, they can run an entire project entirely by themselves which makes them incredibly efficient. This one person can do the work of a small team simply because they know how to do everything. I would prefer that they spend their time teaching others how to do what they do but there is a place for everyone and there’s not one single way that things are done.

Andrew: This is really not based on being a fully licensed architect, but what is your position in a firm? That will have a much larger impact on your daily work. The size of your firm will also impact this issue. If you are in a larger firm, you will most likely be drafting for more of your day maybe. In a smaller firm, you may not spend as much time in your day drafting. The main factor here is where you are in your career path. As my firm grew in numbers, the less and less I did any drafting or project drawing during my day.

Are large firms exempt from the issues small firms have with inexperienced clients and GC’s? jump to 49:38

Question submitted by @leecalisti – Lee Calisti

Bob: No – large firms still have challenges with inexperienced clients and general contractors although there are definitely more challenges in this area on smaller projects. For example, the project I mentioned earlier (in the podcast) that mentioned a current project that has a $540 million construction cost has a gigantic team made up of people who all know what they are doing and are highly skilled at the role they have on the project team. Smaller projects seem to have more challenges and issues because a larger percentage of the leadership team might not have been through this process before – and I can say that I tend to work with a greater variety of general contractor’s on residential projects whereas it’s the same 15 or so general contractors on these giant projects.

Andrew: No, I think you still deal with those issues based on firm size, even at say the size of 50 person firms. It also tends to depend on the type of work you are doing. Public work may have more issues than high-end residential, but both may be less than production-level residential work. So there are similar issues at every level of firm, but they may decrease as the firm grows in size. But let’s be real, no one is exempt from those types of issues in this profession. They are inescapable.

What haven’t you accomplished in your career that you are still striving for? jump to 51:40

Question submitted by @brannonheake – Brannon Heake

Bob: Other than a fat paycheck? There is no shortage of things I have accomplished in my career but if I stand back and survey how things have gone, I gotta say, I think I’m doing pretty well for myself, and answering this question (even thinking about it) makes me a little uneasy … like I am just inviting something terrible to happen that I will then have to go “accomplish.” If I am forced to answer, as an architect that does single-family residential projects, I would like to design my own house. I’m not even all that picky about what sort of house that needs to be – maybe I’ll sell my current home, move into an apartment and then design myself a small weekend cabin in the woods or on a lake. THAT is definitely something I would like to accomplish in my life.

Andrew: As I am changing into maybe my “second career,” it seems these days, I do not have any answer for this question. I am currently working on reevaluating and adjusting these thoughts for myself at the moment. I may have had some ideas when my life was more focused on my practice, but those are being set aside to make way for other possibilities or goals. So, for now, this is a large question mark in my life.

Your iPad Pro first impressions? How do you find yourself using it? jump to 54:56

Question submitted by @nick_t_quinn – Nick Quinn

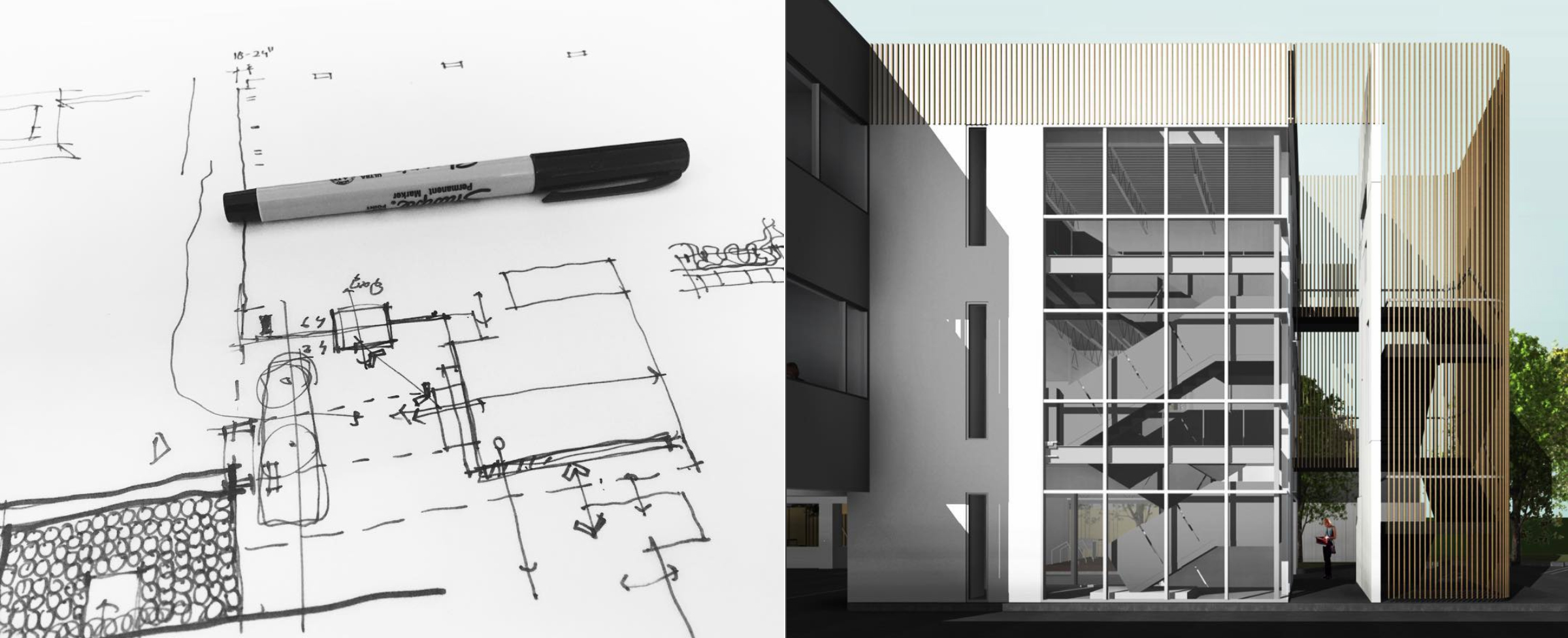

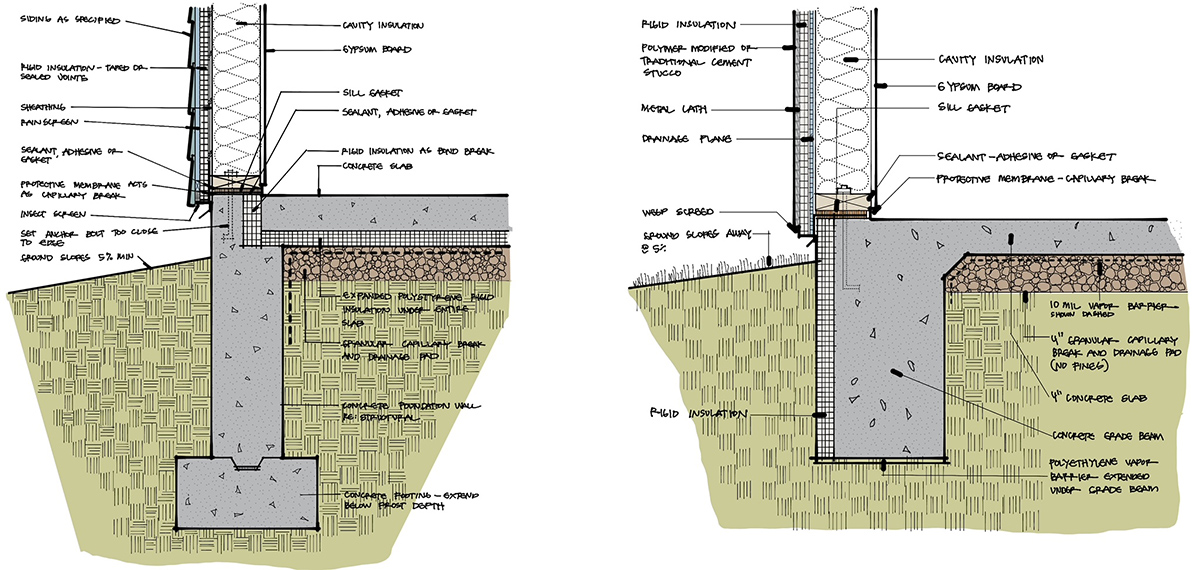

Bob: I fully expected to get some grief from Andrew on this because he has been an iPad advocate for years and I have always been resistant. So what’s changed? First is that there is finally a stylus that works closer to how pens and pencils actually work. Before there was a lag to them that I found extremely off-putting and for the reason (primarily) I hated sketching on the iPad. The other thing that has changed is that there is now sketching software that works the way I want it to work – that feels natural and doesn’t encumber my graphic process. For example, I sketched the two foundation details up above (as part of a teaching exercise) and they look exactly how I would want them to look if I had hand-sketched them. Are there other reasons an iPad is great – of course! With the amount of digital online meetings I have now, I am able to sketch in real-time on screen with people on these calls and basically create digital notes during the meeting.

Andrew: This was really a very Bob-centric question… But I am just glad that I was right all along. I have been telling Bob to make this shift for years. There is nothing more for me to say. Bob will argue that it is much different now than it was years ago, but I will stand by my statement of “I told you so.” Haha!

Retirement Goals? jump to 59:08

Question submitted by Steven Burton [private account]

Bob: Other than knowing that I want to retire, I haven’t spent much time thinking about it as I am still in my early 50s and I’m not counting on winning the lottery as part of my retirement plans. I like traveling – but that’s more about being somewhere else as I don’t actually like the process of getting somewhere else. I would also like to design myself a cabin as I mentioned earlier. Funny how the older I get, the more I look forward to getting out into the middle of nowhere with limited contact with others. I don’t need a lot of people to entertain me, I just want a few.

Andrew: I have been really thinking about this lately. Maybe it was pandemic related, but I have spent more time thinking about this in the past two years than ever before. For me, my current goal is to find a beach or island location and live the rest of my life in relaxation and doing very little. I have bounced around the idea of owning a bar or a scooter rental shop on the beach. The bar seems like less work. The goal would be to just live life and make the ends meet as needed, but not much more. The goal would be to escape the high-pressure rat race that life is for me right now. Time will tell if this changes again as I continue to age and move closer to that time in my life. I would like to say that, as of right now, I plan to retire as early in life as I can. That idea alone tempers my expectations in many ways.

What the Rank jump to 62:42

I think we’ve been a little too positive on our most recent rankings, focusing on the best of certain things so we are going to pivot a bit a go in another direction. Today we are ranking

[drum roll please]….

What are your Worst Three Vegetables??

| #3 | #2 | #1 | |

| Andrew’s Worst 3 Vegetables | English Peas | Cauliflower | Green Beans |

| Bob’s Worst 3 Vegetables | Lima Beans | Artichoke | Eggplant |

Before anyone feels the need to point it out, I am aware that Lima Beans aren’t technically a vegetable … but that’s just how much I dislike them.

Ep 108: Ask the Show (Fall 2022)

There you have it, 10 somewhat burning hot questions that inquiring minds needed to know – hopefully, the rest of you found something of value to the questions selected for this round of ‘Ask the Show’. If you submitted a question and didn’t see it here, no worries as we keep track of all the questions we receive and unless it was something wacky, chance are better than zero that we will eventually get around to answering it for you.

This is the last Ask the Show episode we will do this year so look for your next opportunity to come sometime next spring … start thinking now about what questions you would like to see us attempt to answer!

Cheers,

Special thanks to our sponsor Petersen, which manufactures PAC-CLAD architectural metal cladding systems. Petersen’s products include wall and roof systems in both steel and aluminum. PAC-CLAD systems are available nationwide in 46 standard Kynar-based PVDF colors. Visit pac-clad.com to learn more.