How hard is it to do work for your friends? How has shifting from employee to employer changed the way you approach projects? If you could drastically change one thing about architecture school, what would it be? All this and more on today’s episode as Andrew and I answer your burning questions where almost nothing is off-limits. Welcome to episode 94: Ask the Show – 2022 Spring Edition.

[Note: If you are reading this via email, click here to access the on-site audio player]

Podcast: Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn

Today’s show consists of questions that were submitted through my Instagram account – well, technically speaking, I asked people to submit questions, and we choose about 10 or so interesting ones that we thought we could effectively handle when only allotting ourselves about 5 minutes to answer. If you submitted a question and we didn’t answer it here, it’s probably because your question is either a topic that we plan on really focusing on in a later episode, or was too complicated and specific to you that nobody else would really be invested in the answer, or it didn’t make sense – mostly because it wasn’t in the form of an actual question.

This time around I was a little disappointed that everyone mostly understood the assignment and we received very few that were silly or salacious – that means no underwear color or groupie questions. Since this is the Spring edition of Ask the Show, the title of which suggests that there will be a Fall episode so I suppose you have your chance at getting your questions in – which will also provide another opportunity to see if we answer some personal questions.

Let’s get started and see how many we can get through …

What are the difficulties when doing work for your friends? jump to 3:49

Question submitted by @ericrengale – Eric R. Engle

Bob: Since this question has the word “difficulties” in it, I took that as the focus of the question and ignored the positives and benefits that come from doing work for your friends. Almost all of the difficulties I have ever personally experienced, or have heard about from other architects, occur when the expectations of services rendered do not align with the payment tendered. This is an issue that mostly occurs to young architects due to the fact that their friends don’t necessarily have the money to pay full freight. I have mentioned this on several occasions but if you want the buddy rate, you are going to get what I can give when it is convenient for me to provide them and if you want your project to be a priority, you have to pay the same rate that everyone else.

I am well aware of the fact that this makes me sound like a jerk – and maybe I am (I don’t think I am) – but it just doesn’t seem reasonable that when services and payment are wildly disparate from one another and there is no change in the expectations on deliverables. Clear communication is the key to getting this figured out before any work begins so that strains on the friendship are not introduced.

Andrew: I looked at this from the perspective of doing work as a favor and not as a truly “paid” gig. That part of this equation makes this a tricky situation for some. I think the main issue is making it clear that your favor is exactly that… a favor. So this means it is not always your first or even third priority. It is critical to make these conditions known upfront or that is how situations go bad. Your friends probably hope that you will complete work faster just like any normal client. The issue is that they are your friend so sometimes that feel that creates more of a priority for you to help them. I have never had this go bad for me yet, but there is always time. Make sure that from the beginning you are clear about how this will work for you and that they as your friends understand that if you are providing a favor, it is on your own time. How and what that means for every person is certainly different, but being clear and transparent will at least help. It may even force them to officially hire you or to simply pass on your help. It is the “favors” that can make it tenuous.

What assignments do new graduates get in their first year of work at small and large firms? jump to 10:06

Question submitted by @wilskyy – Kylie Wilson (private account)

Bob: This is a great question but what makes it difficult to answer is that the tasks typically assigned to new graduates can vary wildly between small and large firms. My observation is that new graduates get thrown into the thick of things from day one in a small firm and they tend to work on any and everything that needs to be done. Large firms tend to have a level of oversight at each step along the way and as a result, the responsibilities of new graduates tend to be more granular and specific to a specific objective. New graduates tend to work on design-specific tasks in my large firm because that is supposedly what they are best at doing since that really is what architectural educations are focused on. Eventually, people migrate out of design roles and start to contribute in other ways on the project – more project architect and construction administration work once they’ve had a chance to see how these large buildings come together.

Andrew: I tended to make my newly graduated employees work in the construction and detailing side of projects. It was important to me that new or young employees learn how things get constructed as quickly as possible. This would allow them to require less management from me or more experienced colleagues sooner. I would have them check shop drawings, draw details, come on job site visits with me, and do all manners of things that would increase their construction knowledge faster. Of course, I also had them doing graphical tasks in the office for presentations or SOQ packages. But my goal was always to get them up to speed and knowledgeable about how projects are constructed as quickly as I could. That would then allow me to spend less time “overseeing” their work. It would lead to their “freedom” faster also, which I think most of them preferred.

With a new practice, how do you move from” starter” projects to bigger/better ones? jump to 16:12

Question submitted by @basic.workshop

Andrew: Time. I have no great answer here. Every jump in project scale just takes time and experience. Sometimes luck does play the part, but most of the time it comes down to doing more work and incrementally growing the size of those projects. There is no magic bullet here. This also depends on the type of work you are doing and wanting to jump scales. I can speak from experience in public sector work, time is the biggest measure. Once you have completed 15 to 20 50,000 sq. ft. projects, then you may be viewed as able to handle the 100,000 sq. ft. ones. But if you can land a private commercial project due to a connection or a previous client it might be easier, but I think that doing “good” work matters.

Bob: I agree that time is a major contributor to the answer to this question, but I think luck also plays a role – which is a wildly unsatisfactory answer. It seems like this growth and opportunity takes place by building upon the success of smaller projects – and creating a terrific client experience will lead you to be introduced to new people and new projects. Years ago, I remember the firm where I work had a project that we landed due to a personal relationship between one of the partners and the client. It was a rather large, very modern residential project, and was decidedly bigger in all sense of the word to the work we had been doing previously. The firm did a great job on that project and we subsequently were able to leverage that project into similarly large modern projects it seemed to prove to others that we were capable of performing at this level. Getting the next project, and the next, and the next became easier and easier

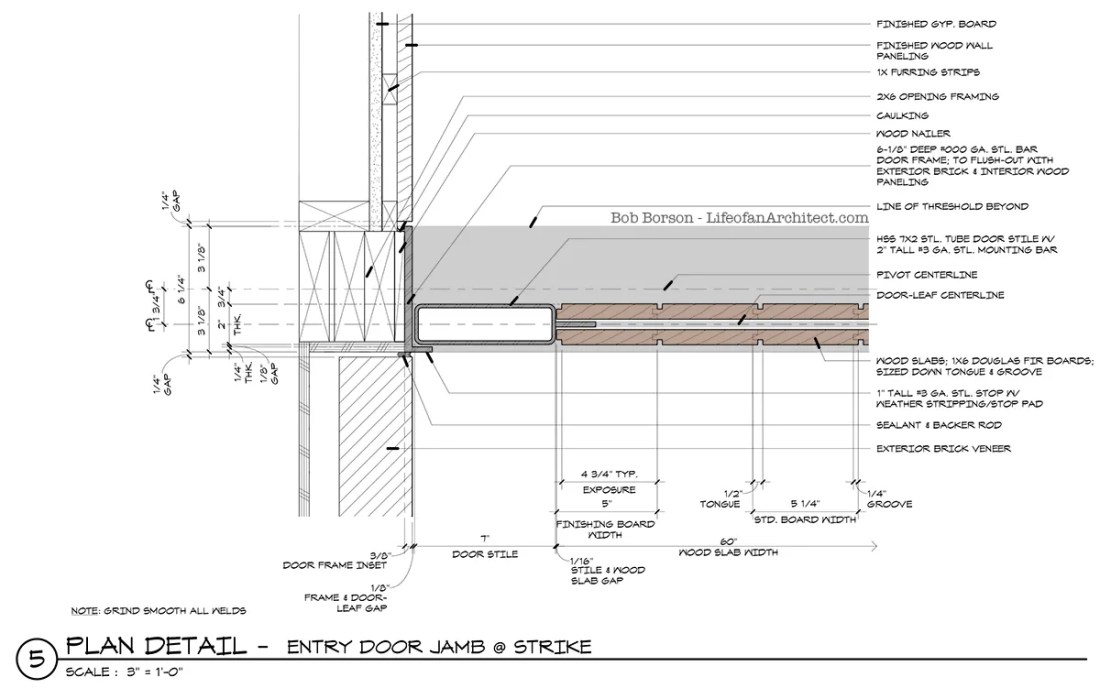

Best way to study architectural details? jump to 21:09

Question submitted by @millennial_archi_student – Cobus Visser

Bob: Andrew and I basically had the same answer for this question – find a way to connect the drawing to the built reality. It is important to understand that the lines you are drawing have a specific role to play and seeing how those manifest themselves on a job site will exponentially speed up your knowledge of detailing.

I have tons and tons of books sitting in my library that have drawings and details in them – it’s really one of the major criteria I have for the books that I purchase. I have long wanted to reach out to architects whose work I admire and ask them to send me examples of their drawings … but I know that people generally frown upon sending out documentation to a stranger since they don’t know what I really plan on doing with those drawings. It’s part of the reason I share a lot of the drawings I do, despite people telling me that I am crazy for doing so, because I remember wanting to see how things were done and I didn’t have anyone to help teach me how to create them for myself.

Andrew: Look at books. Find details. Study them as much as you can. Draw them and redraw them. But then also make sure to see them in person. Look and watch things get built. Got to construction sites. Even if they are not your projects. Even if they are not projects from your office. You can watch the construction from the street if needed. I don’t think that is a bad thing. Who knows you might find a job site superintendent who is a friend. I am not proposing trespassing, but it is very possible to see construction in almost any location in the world. Understanding not just the materials and applications, but the sequencing is just as important to understanding architectural detailing. Just because you can draw it does not always mean it can be built or built effectively. So the timing of construction is just as critical as the materials.

How to delegate tasks in your firm when you’re used to doing everything yourself? jump to 29:20

Question submitted by @rtoledo80 – Rodrigo Toledo

Bob: When I worked in a small firm, I never had to ask who was going to be responsible for one thing or another because I knew that it was going to be me. When I moved over to my current office, the roles were more specifically identified and everyone had a role to play within the context of the large scope of the work … and I struggled to find my place a bit. I wanted to contribute but didn’t want to move out of my lane and I found myself a little stagnated because I spent time thinking “Should I be doing this? Who is supposed to be doing this? I don’t think I’m supposed to be doing this …” and so on. After about a year, I finally realized that most of the time I could pretty much do whatever I wanted and the people who took on the task to simply get something done without worrying about who was supposed to be doing what – those tended to be our very best performers and the people that were the most coveted in the organization.

Which doesn’t really answer the question.

Successfully delegating tasks really comes down to trusting the individuals you have in place to do their job. They might need support, which is okay because as you move up the chain of command, your job becomes more and more about putting the right people in the right place, and then giving them the tools they need to be successful. Delegating work amongst team members will also help build ownership in the final product and as a result, people tend to care more about the role they are playing.

Andrew: Little by little. As a firm owner who was admittedly forced to operate as a solar practitioner for the first few years and then let go of things as I added more employees, I can understand the difficulties of letting go. I tended to select the things that took more time or that I was willing to let go of eventually. I knew that my time was not best spent producing drawings. So I had to teach my preferred methods and then oversee them until I was able to simply relinquish them almost completely. I still would review them, but much less than before. I also was forced to give up tasks because I had to prioritize. Some tasks are just “below” your pay grade at some point. This definitely increases with the number of employees. At some point, I had to imagine that my business was my architectural project and that is what I had to manage, not the individual projects, tasks, or even people. I will say that this was one of the most difficult things I had to accomplish as a firm owner. It is not easy, but in order to grow or be successful, it is usually necessary.

How has shifting from employee to employer changed the way you approach projects? jump to 33:53

Question submitted by @campaign.mo – no posts

Bob: I went from being interesting in knowing more about business operations and the client experience, to actually having to make decisions about the direction of the company based on these things. Sometimes it is as simple as taking responsibility for the project budget (which in the current construction landscape is downright impossible at times) to ensuring that I have the right people in the right roles on the project while balancing billing rates, abilities, employee growth and development, and financial health for the firm.

Andrew: For me, this is simply one word. Responsibility. As an employee my level of responsibility was limited. I had to only really worry about my work, tasks, and projects. Once you are an employer, you’re then responsible for everything. So it was just an increase in that level of responsibility. The question is specific to projects, but I am not sure I can isolate that in a sound manner. But I think it possibly changed my perspective on projects that were necessary, good, and desired. As an employee, I only wanted those “desired” projects. As an employer, I knew every office takes all three types. So the lens through which I evaluated projects was skewed in a different way. I was responsible for all the projects but also all my employees and their livelihood. That changed my perspective on what projects actually did for the firm.

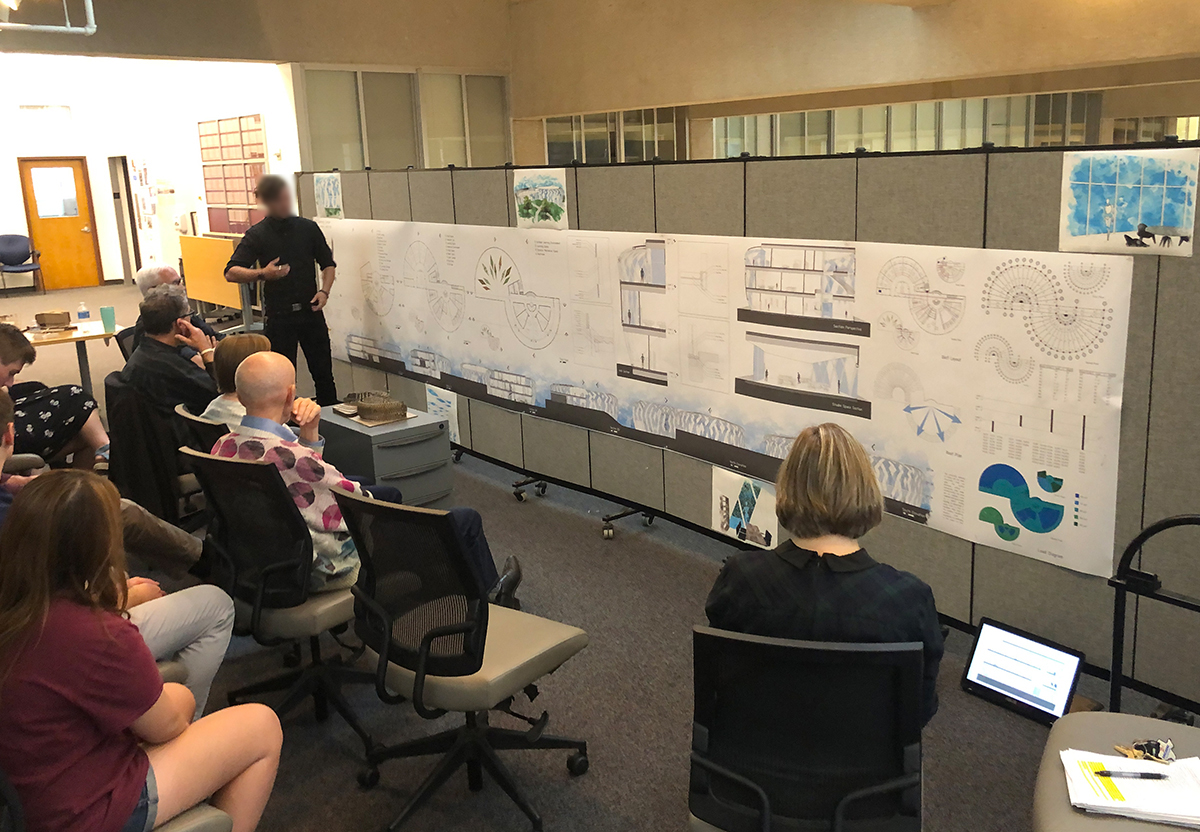

Collaboration is key to the design process … do you think it is viable to do so in the WFH or hybrid scenario? jump to 40:51

Question submitted by @iamsethshelman – Seth Shelman

Bob: This really comes down to firm culture and collaboration and whether or not you believe that you can successfully maintain or develop these things when people are not actually in the same space as one another. Given that the question provides us the luxury of considering a hybrid scenario in addition to a true work-from-home situation, I am going to say that I am not a fan of a true WFH work policy, but I am all for a hybrid scenario. The question comes down to the level that you believe that people can be out of the office and still be a part of a culture that typically benefits from in-person nuances. I also don’t believe that there is a one-size-fits-all policy that would work. At my position, I think I could manage maybe 1 day a week out of the office because so much of what I do is specific to working directly with others. The folks that i work with could probably be the exact opposite of that and could effectively be out of the office as much as 3 or 4 days a week. I’m not sure how convenient that would be for me because I would like to engage with these people face-to-face, but I recognize that things are changing and this is probably the trend of the new normal.

Andrew: I think that it is possible to collaborate in a digital world. But I also know that it works better in person. My experience over the past two years of pandemic online teaching and now moving back into in-person teaching has solidified my thinking on that idea. Students are not quite as knowledgeable and don’t quite comprehend things the same. I know this sounds like “old man” talk, but I think it is the truth. I do think it can work as I even had remote employees in my office way before the pandemic, but they would still come to the office. I think some arrangement of hybrid is possible, but entirely remote is not, in my opinion, possible in our profession. There is too much that cannot be communicated via emails and online video meetings. Coming together to collaborate in the same physical space is essential to successful projects, yet that could be only once a week. Granted I will sidebar here and say that I think this WFH movement is more about flexibility than it is simply a strong desire to work from home.

From the podcast episode, Grand Poobah is the name has come to be used as a mocking title for someone self-important or locally high-ranking and who either exhibits an inflated self-regard or who has limited authority while taking impressive titles and is a satirical term derived from a character “Pooh-Bah in Gilbert and Sullivan’s 1885 comedic opera The Mikado … but I learned it from the 1962 episodes of the Flintstones that I saw in syndication sometime in the mid-1970s as seen here.

If you could drastically change one thing about architecture school or licensing what would it be? jump to 51:07

Question submitted by @natethenrie – Nate Henrie (private account)

Bob: I am going to ignore the licensing aspect of this question since we have an entire show dedicated to the topic (Reimagining the Path to Licensure – Episode 086) and focus specifically on the architecture school portion. To put it briefly (because we do have an entire episode on this topic scheduled for this year), there appears to be a disconnect between what graduating architecture students believe their experience will be once they enter the workforce and that reality. Too many students come out of school with a jarring lack of knowledge regarding what we actually do for a living. I am aware that our path to licensure involves an internship where the profession continues to educate the freshly graduated student on the nuances of professional practice. I am also aware that many architecture schools have formed the foundation of the educational system on the premise that they will teach you how to think critically and focus on the items that the more practical professional experience will not focus on … but few students are prepared for the difference between their studio experience and the realities of practice.

Andrew: Since we overlooked the licensing bit, I think the notion of practicality or professional exposure is a critical component missing from architecture school. I have been “preaching” this for years; even before I was a studio professor. There are certain bits of practical and applicable knowledge that are completely overlooked in school to the detriment of the students. Far too many students graduate and have no idea how the professional really works for what it really takes to do our job. Too many have a limited understanding of all the different areas within the profession. The fact that we are a service industry and that your profession is about generating someone else’s project is often not presented to architecture students. I am not advocating for a technical degree move, but just one that introduces the reality of the profession to students prior to them graduating school, starting work, and then becoming disenchanted/disappointed by the practical truths of the profession. This happens more than you might think

Because the Winter Olympics are currently taking place, we decided to theme today’s would you rather question appropriately.

Would you rather? jump to 58:58

Would you rather Win an Olympic Gold Medal or host an extremely popular podcast?

This might seem like an obvious question at first pass, but there are some nuances to it that speak to longevity. These two choices may have more in common once they are directed a bit. But in a rare instance, Bob and Andrew ended up in agreement on the choice here. It was for different reasons, but still an agreement. So that must mean there is only one true right answer.

EP 94: Ask the Show – 2022 Spring Edition

So this wraps up yet another ‘Ask the Show episode and post. As usual, we received more questions than we had time for and those were added to the ever-growing question bank. It is impossible for us to respond to all of the submitted questions, of course, but we may use some of them for future episodes or blog post topics so don’t lose hope. We still want to try some type of “live” event, and now that the pandemic is becoming more manageable or even the norm, we will look to rededicate some efforts to make this a reality. Also as it seems obvious, we will try to have another round of Q&A in the future this year. Is twice per year enough? should it be more? Let us know what you think and start storing those questions up for the next edition.