When we were all in architecture school, we made a ton of architectural models, but once we graduated … no more. What happened to all the architectural models? Why did 90% of us quit making models? There’s a case to be made in the value of building models and that is the topic of today’s conversation. Welcome to Episode 87 “Architectural Model Making”

[Note: If you are reading this via email, click here to access the on-site audio player]

Podcast: Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn

Classic Model Making Materials jump to 3:08

There are many materials that make up the typical architectural model but when you use one over the other seems to do with either the cost or the time in the process when the model is made. As a student, I made the vast majority of my models out of chipboard because it was readily available and I could buy a sheet of chipboard for less than one dollar. Cardboard was also readily available but was typically reserved for when I needed mass or some structural consideration for my model.

The fancy model materials were always museum board (which to this day I don’t really care for) and basswood. Museum board is a through-body material that is typically seen in white – but the reason I don’t like it is that you have to keep it clean – which always seems like a herculean task and rarely achieved. Basswood was always what was used when you wanted a finished product and was rarely used on study models.

The biggest part of our conversation was actually on glue – that’s right, glue. If you have been through this process you know how important it is to use the correct glue based on the material you are gluing. Here are the major takeaways:

- Hot glue guns are overrated – I am 100% that unless you are gluing fabric to something else, the 10 billion glue strings are not worth the effort.

- If you don’t like using white glue (Elmer’s) you are probably using more than you should

- spray adhesive or rubber cement should be used when you are working with paper

Old School versus New School jump to 12:26

One of the major differences that have taken place since Andrew and I were in school is the use of a laser-cutter. I don’t have a lot of any familiarity with using them but in his capacity as a professor, Andrew sees them being used as a matter of course. The part of the conversation I was interested in was the efficiency that they provide – if any. The short version is that the students have to take a few extra steps to prepare a 3-dimensional model in order to send the required information to the equipment that will cut the pieces out for them. They still have the up-front work in the modeling, and they also have the back-end work in the assembly so I’m not so sure that it actually does save them much time. More elaborate pieces that are all cut true and square – yes this is certainly a benefit.

The obvious shortcoming that I see with this process is that it only seems useful at the end of the process when you might be building a finished model. When we discuss that as architecture students we were constantly making models, the vast majority of those models were study models that were crafted as exploratory exercises and typically only took a day (or two at the most) to prepare. What you sacrificed in accuracy you made up for in expediency.

When do you get to build a model? jump to 22:52

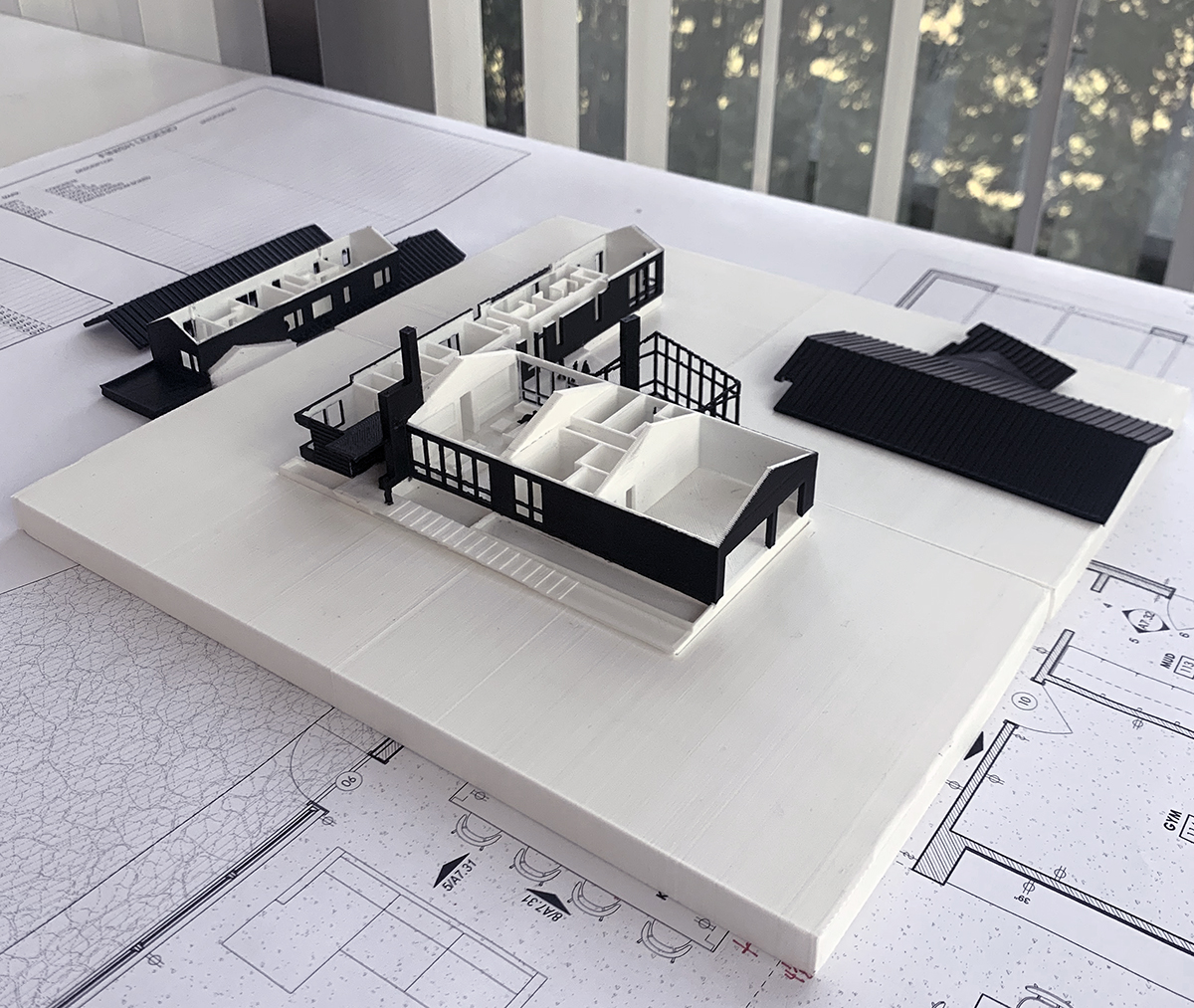

This was a logical transition in our conversation as we moved from our time as students and started to discuss the roles that models play in a professional office. What sort of projects make sense to use models and is there a scale consideration? The vast majority of models that I have built (or had built) once I entered the working world were projects that had smaller footprints. Residential, small multi-family, light commercial … nothing that exceeded 20,000 square feet or so. As a result, these models were typically built as design exercises to help us in working through the building massing or to use as communicative tools when meeting with clients. Occasionally we will do some blocking or massing studies during the schematic design period – but those are typically site-focused and the models are extremely blockish in their articulation.

During this episode we talked about the model that I nicknamed “Voltron” which was a gigantic 12′-6″ x 5′-0″ model that was built in twelve different pieces that could all pull apart – maybe I should say they “had” to pull apart. This model received quite a bit of attention but you can see how it was built, assembled, and photographed best in this post but you can watch the assembly process below without having to jump over to that other article.

You are probably thinking “That model is humongous!” (if “humongous was a word that anybody still used) and you are correct. You might be surprised to learn that this was only about 25% of the house as my partner who designed it did so as an exercise to study joint patterns and material scale – this was well past a massing study. The question that everyone always asks is how much that model cost … and I don’t actually know. I can tell you that there were two summer interns that completely dedicated their time to its fabrication for about 2 1/2 months, which means that it wasn’t cheap, but compared to the actual cost of the house, it probably wouldn’t even register on a line item.

Are models expensive to build? jump to 29:45

Another good segue so we moved on to discuss a little about the expense associated with building models. We built a scale model of a modern residential project and as I recall, she put this model together in less than a week, and her hourly rate was $35/hour (because if you interned in my office, you do real work and we charge real money for your efforts … it’s just not a lot of real money). If she was 100% billable – which I doubt she was – her billing rate (for labor) for the week would have amounted to $1,400. Let’s throw in another generous estimate of $300 for model materials, which brings the grand out-of-pocket total of this model to $1,700. When I compare this amount to what our fee might run on any project of this size and scale, the cost of this model represents 9/10ths of 1% of the total architectural fee.

We spent some time talking about how the presence of architectural models in an architect’s office helped set the tone for the culture in that space. There is no question that architectural models draw people to them like to proverbial moth to a flame and in one instance, we were contacted by a production studio that had seen one of our models here on the site and wanted to rent a particular model for use in an upcoming episode they were filming. They came and picked the model and returned it a few days later and when the episode came out, we had a watching party at my house. If you’d like to see the clip, or what eating barbeque at my house, looks like, just click the “A Culture of Models” image below.

The movie that Andrew mentions was ‘Life as a House‘ and you can see part of the scene where the architectural models are getting smashed here.

Is there an advantage to Physical Models over Digital Renderings jump to 47:10

If I put a stack of 3D renderings on the table and pointed at the images while telling my story, there would be a period of mental gymnastics that our clients would need to jump through as they orient and reorient themselves to the project as we switch through all the different images. Not every client can manage this gymnastic routine with the ease of our architectural understanding of space. So a major difference when using a physical model for this type of process is that it is typically easier to follow. With a physical model, the understanding is instantaneous and constant.

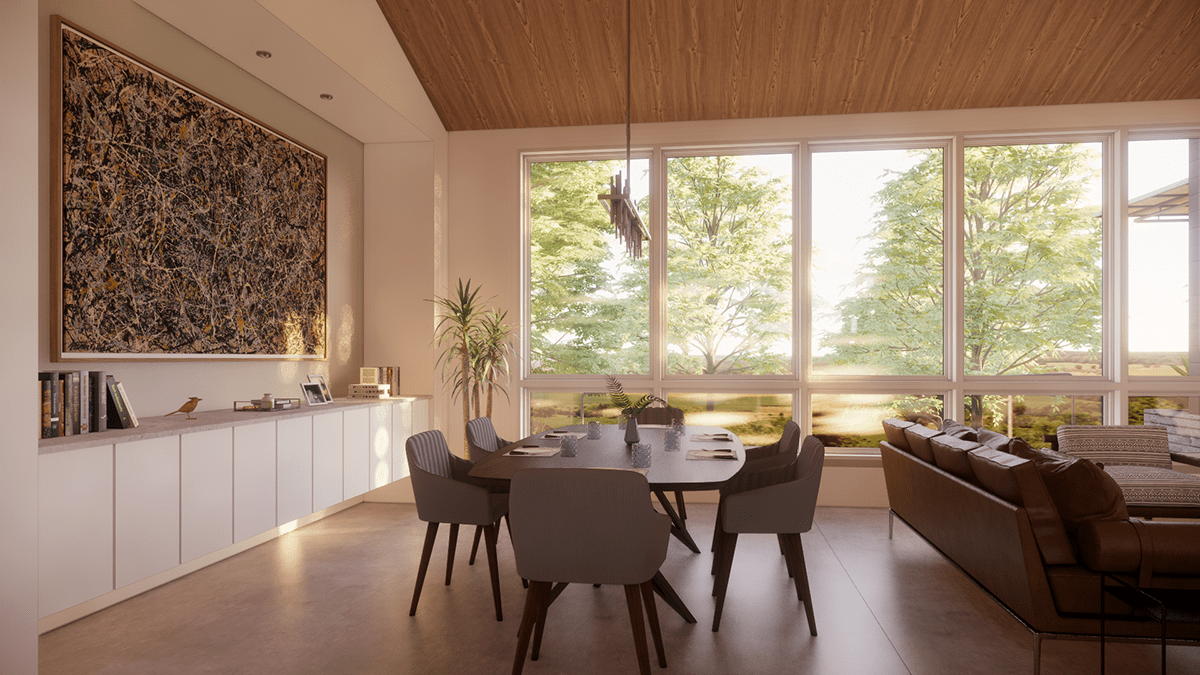

I have changed my tune a bit on the positive role that digital renderings provide but the real value comes when we work live in the digital model during the meeting. This deals with the reorientation challenges that static images present. I wrote a post earlier this year titled “Renderings for Residential Design” The real advantage that these renderings have over a physical model take place on the interior or the space – the things that allow the people we are presenting to understand how their lifestyle would fit into the project. The ability of physical models is limited in this capacity to provide a higher level of interior detail and aesthetic understanding within these spaces. It would take a very large-scale model to convey the same depth of information. The digital modeling and rendering win this hands down.

Would you rather? jump to 57:35

Would you rather … give up eating dessert or fast food?

This is either a completely easy answer or a coin toss and your answer to this question is locked into your formative development years. The thing that might surprise most people is that the first time I ever ate at McDonald’s I was 26-years-old.

Architectural Model Making

It isn’t a stretch to conclude that Andrew and I are both fans of architectural models and the contributions they make to the design process. While other mediums such as renderings and virtual reality have started to make a play for my attention, none of those other presentation devices have the impact that a model brings to the table (literally and figuratively). While I can appreciate the effectiveness that renderings bring to the communicative process – it’s hard to email a model – and I simply like having models around the office. They make me feel like an architect, and to my visitors, I think it’s what they expect to see as well when they come in for a meeting.

Cheers,

Special thanks to our sponsor NCARB, which is conducting a profession-wide study called the Analysis of Practice. If you are an architect, or in the process of becoming one, your participation is valued and important in shaping the future of the licensing process. Please visit ncarb.org/AOP and be a part of the change you want to see.